A New Zealand explorer who trekked in West Papua before Indonesian rule says he is saddened to see what colonisation has done to the region’s indigenous people.

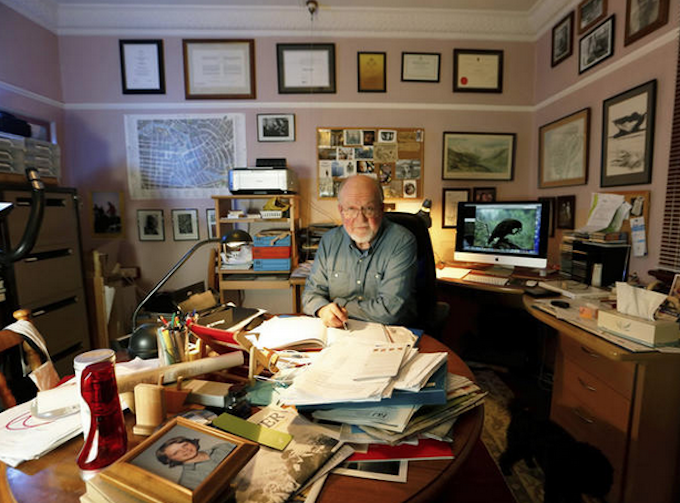

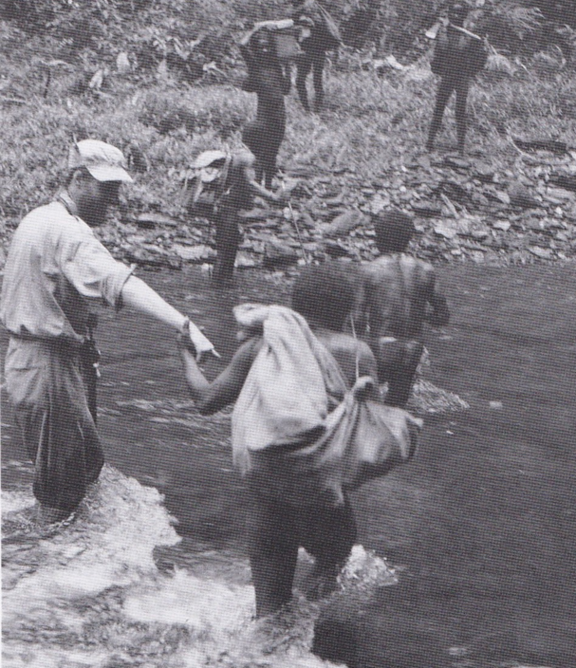

Philip Temple, who is also a renowned author, was part of a small group who made the first recorded ascent of the Carstensz Pyramid in West Papua in 1962 before Dutch colonial rule ended.

“The Dutch had already given [West Papua] its own flag and all that sort of thing. And in fact when we made the first ascent of the Carstenz Pyramid, that was the flag we took to the top,” he said.

- READ MORE: Indonesian lawmakers adopt unpopular bill to reshape Papua

- 714,000 Papuans, 112 organisations oppose ‘failed’ special autonomy law

- Other reports on the special autonomy law for the Papua region

“It was a West Papuan flag that made it to the top, not an Indonesian flag.”

Temple said it was sad to see ongoing human rights violations against West Papuans, and their marginalisation in their own homeland due to transmigration of settlers from other, heavily populated parts of Indonesia.

He also cited the violence and displacement suffered by the indigenous people of Papua’s highlands due to ongoing conflict between Indonesian security forces and pro-independence fighters.

This was the remote interior region where Temple explored six decades ago. Today it is also a resource-rich region where the one of the world’s largest gold mines, Grasberg, operated by US company Freeport McMoran, has been in operation since Indonesian administration began, producing major revenue for the state while devastating the environment.

Papua example of modern colonisation

What has happened to the territory, according to Temple, is another example of modern colonisation.

“There’s quite a thing going on in New Zealand at the moment about the effects of colonisation, and yet not that far away in the geopolitical sphere, it’s happening right now,” he said.

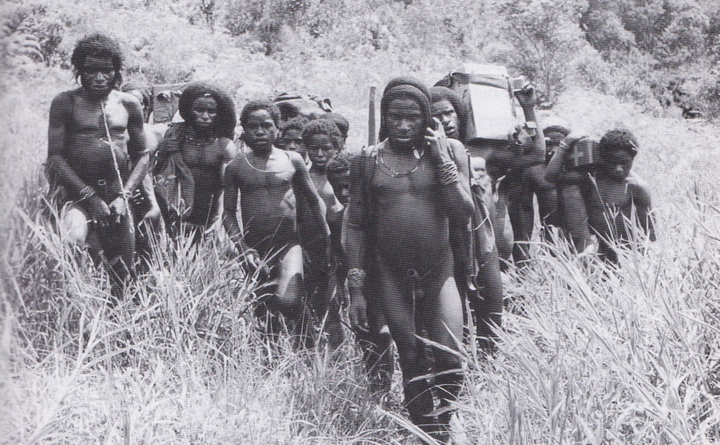

“What is really distressing for me is that the Dani people, who I got to know pretty well, they’ve been completely taken over by Indonesian settlers, especially in the Grand Valley, the Baliem, and they’re now treated as kind of curiosities by Indonesian visitors and so on.

“It’s the same kind of thing that happened to Māori at the end of the 19th century.”

Temple said that the New Zealand government’s reluctance to upset Indonesia by pushing for a resolution of the conflict in West Papua is at odds with its obligations to support the rights of indigenous Pacific peoples.

He said there was a lot that New Zealand could do, including raising the issue at the United Nations level, and also review defence ties it has with Indonesia, as well as military exports to Indonesia.

NZ ‘closely monitors’ West Papua

A spokesperson from New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade said it continued to closely monitor developments in Papua.

“For example, earlier this year the New Zealand Ambassador met virtually with local government and civil society leaders in Papua,” he said.

“We support the PIF (Pacific Islands Forum) Leaders’ call for the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to be permitted to visit Papua, in a manner that is safe and consistent with covid-19 restrictions.

“New Zealand recognises Papua as part of Indonesia’s sovereign territory. We encourage Indonesia to continue with its efforts to deliver on the goals and principles underpinning special autonomy for the benefit of all Papuans, including its recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples in Papua.

“New Zealand continues to encourage Indonesia to promote and protect the human rights of all its citizens. We take appropriate opportunities to raise concerns with the Indonesian government.”

Temple has written dozens of books, including The Last True Explorer: Into Darkest New Guinea, published by Godwit in 2002, which details his exporations of unmapped swathes of central New Guinea Highlands.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.