By Khalia Strong

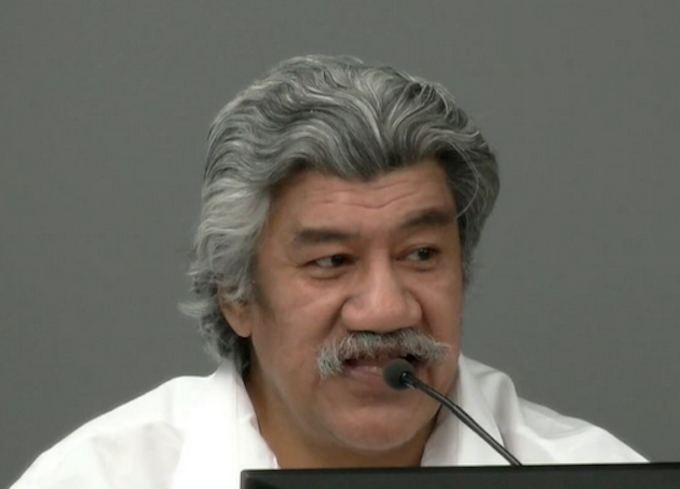

Hakeagapuletama Halo walks into the courtroom. He is a head taller than most, dressed in a crisp white shirt. He has a nervous smile and bright, eager eyes.

Known as Hake to his family and friends, this is not the first time he has detailed the abuse he suffered at Lake Alice. But, as part of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, it is the first time he’s been able to do so publicly.

He said there was no warning or explanation the first time he received electroconvulsive shock therapy, just one week after arriving at the Lake Alice Institute.

“They called my name out. I went freely and walked up the stairs of Villa 7 because I did not understand, I thought it was something to help us patients, but I had a funny feeling something was not right.

“Dr [Selwyn] Leeks and three other staff members were there. They did not ask me any questions or explain anything to me. They just put me on the bed.”

Halo remembered seeing a bed with a small machine on a trolley, with electric earphones that were wet and placed on the sides of his head.

“I looked up at their faces, they were pretty mean looking and that made me feel something was going to happen. I asked Dr Leeks if this was going to hurt and he said, “yes, it is”. I cried and said, “I don’t want it please”.”

Lost consciousness

With no muscle relaxant or anaesthetic, the staff held him down as the volts went through his body and he lost consciousness.

The next time it happened, it was a shock to discover that he remained conscious and felt everything, saying it was like being hit by a sledgehammer.

“The pain was so bad, that when a person was lying down, when they turned it on, I could feel myself actually sitting up. Your body is off the bed… you’re straining to raise your arms but they’re holding you down. And they turn it off, that’s when you’re crying…without the mouthguard, a person would end up biting his tongue off because of the pain.”

The shocks were administered three or four times before the child was taken to a different room to recover, but the effects would be felt for days.

A terrible secret

Halo said everyone knew what was going on, but it wasn’t talked about.

“Us kids, we know that somebody’s always getting ECT because you can hear the screams from upstairs coming downstairs to us kids. In the lounge, in the sitting room, TV room, you can hear them screaming, even the workers that are working around there.”

He says while most of the staff and workers were white-skinned, there were a few cleaners that were Pacific Islanders.

“They can hear it. They’re doing their jobs and crying at the same time because they know what’s going on.”

In addition to the electric shock treatment, the children were injected with paraldehyde, a medicine that was used to treat convulsive disorders.

Halo said they had different amounts injected, based on their behaviour, such as not listening or fighting, even laughing too loudly.

“Paraldehyde is just like another way of giving us a hiding. Using the injection, it is painful, the pain is bad. The child is walking like a pregnant lady sometimes, swaying from side to side, coming out of the sick bay with his pants still halfway down, crying his eyes out – and that’s only for 5cc.”

One teacher trusted

There was one teacher who he trusted at the school, who will later testify as part of the hearing.

“She said to me, ‘you don’t belong here’. She gave us advice, encouragement and counselling. I had not done anything big or really wrong, just the shoplifting.”

Many buildings have been demolished since the institute was closed in 1999. Photo: Fergus Cunningham 2011

A child’s plea for help

Halo wanted to tell his mother about the abuse, and tried to come up with a coded way to tell her.

“I write in my letter in English that everything is alright…they said I have to write my letters in English and take it into the office and leave it open like that for them to read.”

After his earlier attempts to draw a sad face weren’t accepted, Halo learned he had to draw a person with a happy face, but included a speech bubble saying his true feelings.

“I wrote just a short few words in Niuean, saying mum, electric shock, so painful to me. Or, Mum, the people have given me electric shock… injection… I am crying.”

Years later, he would try to recreate these drawings in his journals.

When asked why his mother did nothing at the time, he said there was a language and cultural barrier.

“Because my mum was not an English speaker, she did not know how to get help or intervene…she felt powerless.”

This was not the first time speaking English as a second language had been a barrier.

Misunderstood from the early years

Born in Niue, Halo sailed to Sāmoa on the Tofua, then flew to New Zealand with his grandparents, who raised him for many years.

He had epilepsy as a baby but grew out of it as he got older.

When Halo started at Richmond Road Primary in 1968, he could only speak Niuean.

“I did not understand anything the teacher was teaching. I did not do my homework because I did not understand my teacher and I did not speak in class….I felt totally lost. It was pretty hard to find friends, so I just kept to myself.”

The teachers thought Halo had a disability and put him in a class for children with special needs, where he would act up. When he was 8, an incident with a relief teacher at Beresford Primary that would change his life.

“We were practising songs, and I wasn’t singing properly, just trying to sing but not really good and not participating properly and my teacher got upset…so she came and took me out of the classroom.

“I was scared about being locked in this dark room. I tried to push on the door to push it open and let myself back in, and my hand accidentally went through the glass door.”

Cut his hand severely

He cut his hand severely and was taken to Auckland Hospital by ambulance.

The school report said he violently punched the window but the scars on the palm of his hand prove he did not punch the glass, but was pushing on it.

After this incident, Halo was seen as being violent, and was referred to St John’s Psychiatric Hospital in Papatoetoe.

From there, he spent a few months in Niue, before returning to New Zealand and moving between several schools, his behaviour worsening after the death of his grandfather when he was 10 years old.

He appeared in the youth court because of a shoplifting offence, and was sent to Owairaka Boys’ Home in October 1975.

“I was put in a secure room for four days. I had to stay there for a long time because I was so upset. They were worried I would run away. I was lonely,” he says.

“In the secure room there was a bed, a toilet, and sometimes another kid was put in the same cell. When that happened, we had to share the toilet and we had to eat in there too. I did not like that room.”

Some children targeted

Along with physical violence, the staff were strict and some children were targeted more than others.

“The boys that had to do the cleaning and cooking did not go to school. I was one of those kids. I had to do the jobs. I had no choice.”

He was then referred to Lake Alice, a mental hospital in the Manawatu District that had been converted for youth.

“My [grandmother] and my birth parents were told they were taking me to Lake Alice to go to a school there. They were not told that it was a mental hospital. They never knew the true story.

“My mum did not speak good English at all and there were no Niuean interpreters. She signed papers because they told her they were taking me to a school.”

Arriving at Lake Alice on 6 November 1975, Halo said he was surprised and scared.

“My first impression was “bloody hell, what is this place? What sort of place? This is not a school, this looks like a prison!”

Some not documented

An estimated 300 teenagers were admitted to the institute across the six years it was operating, but there are thought to be at least a hundred more who were not documented, with some children younger than 10.

It wasn’t until after Halo was discharged in 1976, when his grandmother arranged to legally adopt him, they discovered he had been made a ward of the state.

“The interpreter at that meeting explained to my Mum [grandmother] what a State Ward meant. My Mum had not understood, and no one had ever interpreted for her, that the state had the rights of guardianship over me.”

Thinking back to the start of the year when he was referred to Lake Alice, Halo said his Mum had not understood the social worker at the time.

“There were no interpreters there to assist my Mum in this conversation. The social worker thought my Mum wanted social welfare to have full control and have me under their guardianship,” he says.

“However, my Mum was misunderstood. She had asked him to please look after me, while I was in care. The social worker thought she was saying `please take Hake and make him a State Ward’.”

Halo says if a Niuean interpreter had been present, he may not have been returned to Lake Alice, or later referred to Carrington Hospital in Auckland.

Now elder in his church

Halo is an elder in his church and attributes his healing and strength to his faith.

His epilepsy returned after his time at Lake Alice, making it difficult for him to hold down a job, although he did work at a facility packing plastic bottles, but found the static electricity a trigger for his traumatic memories.

He is on a benefit, but says the Ministry of Social Development is trying to get him onto the jobseeker benefit.

When asked about whether an apology would help, he said he didn’t need a personal apology, but wanted to see an acknowledgement of how Pacific Islanders were treated.

“The state should have explained to me and my parents what a State Ward was and what happens to a child who is a State Ward. If they could not understand English, they should be offered an interpreter. The state should tell us the truth about where our children are going and what is happening to them.

“Looking to the future, if I was told a grandchild of mine had to go into an institution, I would say ‘no way’. Our children have to be with us, not in institutions.”

At the hearing, a handful of survivors were present to support Halo, Paul Zentveld acknowledged those who could not be there.

“All these many years when no one but a tiny few believed us. Officials of Government did not really care what happened to us as children while in Lake Alice in the 70s. We have done many things over the years, including alerting the United Nations and here we are.

“We stand before the survivors of Lake Alice, ready to tell our story publicly for the first time. Those who cannot be here are here in spirit.”

But the man responsible for the mistreatment of hundreds of children, may never be held to account.

‘I represent a man incapable of instructing me’ – lawyer for Dr Selwyn Leeks

Hayden Rattray, counsel for Dr Selwyn Leeks, appeared via Zoom to deliver the news many were expecting.

“Dr Leeks is 92 years old. He has metastatic prostate cancer … heart disease, chronic kidney dysfunction.

“Dr Leeks is neither aware of the matters of the inquiry nor cognitively capable of responding to them. The reality is I represent a man incapable of instructing me.”

Rattray referenced an assessment in April by neuropsychologist Dr Sarah Lucas, which also reported signs of Alzheimers and dementia.

As a core participant in the inquiry, Dr Leeks has the right to give evidence and make submissions, however, “by virtue of his age and cognitive capacity, manifestly incapable of doing either”, Rattray explained.

Assisting Counsel Andrew Molloy said, along with Dr Leeks, other parties needed to be held accountable.

“While numerous eyes have been cast over these events over the years, we’ve never previously pulled together the strands to compile as full a picture as we can … While individuals may have spoken of this here and there, their voices have never been heard collectively by us as a society.”

Queen’s Counsel Frances Joychild said the inquiry was exposing a “collective shame”.

“It’s an inquiry into a dark and shameful seven year episode in the history of state care for vulnerable children in this countr …. The damage to the national interest is impossible to calculate.”

The Lake Alice hearing runs for two weeks. Twenty survivors are expected to give evidence, along with former staff members, medical experts and police witnesses.

More information:

The Royal Commission will examine abuse and neglect of children and young people in residences run by the state between 1950 and 1999.

The scope of the inquiry covers abuse that happened in State care such as foster care, police cells, court cells or police custody, schools or special schools, disability care or facility, youth justice placement or at a health camp.

They are also looking at abuse that occurred in faith-based settings such as a religious school or church camp.

Witnesses can speak anonymously about sexual, physical and psychological abuse and the effects it has had on them in later life.

The Pacific Investigation encourages Pacific survivors to continue coming forward and engage with the Royal Commission of Inquiry.

To contact the Pacific Investigation, please email: Reina.Vaai@abuseincare.org.nz or call us on 0800 222 727.

For further details please see www.abuseincare.org.nz.

Pacific Investigation hearing dates: July 19-30, 2021

Hearing location: Fale o Samoa, 141r Bader Drive, Māngere, Auckland 2022

Khalia Strong is a Pacific Media Network News journalist. This article is republished with permission.