ANALYSIS: By Ramzy Baroud

The notion that the covid-19 pandemic was “the great equalizer’ should be dead and buried by now. If anything, the lethal disease is another terrible reminder of the deep divisions and inequalities in our societies.

That said, the treatment of the disease should not be a repeat of the same shameful scenario.

For an entire year, wealthy celebrities and government officials have been reminding us that “we are in this together”, that “we are on the same boat”, with the likes of US singer, Madonna, speaking from her mansion while submerged in a “milky bath sprinkled with rose petals,” telling us that the pandemic has proved to be the “great equalizer”.

“Like I used to say at the end of ‘Human Nature’ every night, we are all in the same boat,” she said. “And if the ship goes down, we’re all going down together,” CNN reported at the time.

Such statements, like that of Madonna, and Ellen DeGeneres as well, have generated much media attention not just because they are both famous people with a massive social media following but also because of the obvious hypocrisy in their empty rhetoric.

In truth, however, they were only repeating the standard procedure followed by governments, celebrities and wealthy “influencers” worldwide.

But are we, really, “all in this together”? With unemployment rates skyrocketing across the globe, hundreds of millions scraping by to feed their children, multitudes of nameless and hapless families chugging along without access to proper healthcare, subsisting on hope and a prayer so that they may survive the scourges of poverty – let alone the pandemic – one cannot, with a clear conscience, make such outrageous claims.

Not only are we not “on the same boat” but, certainly, we have never been. According to World Bank data, nearly half of the world lives on less than US$5.5 a day. This dismal statistic is part of a remarkable trajectory of inequality that has afflicted humanity for a long time.

The plight of many of the world’s poor is compounded in the case of war refugees, the double victims of state terrorism and violence and the unwillingness of those with the resources to step forward and pay back some of their largely undeserved wealth.

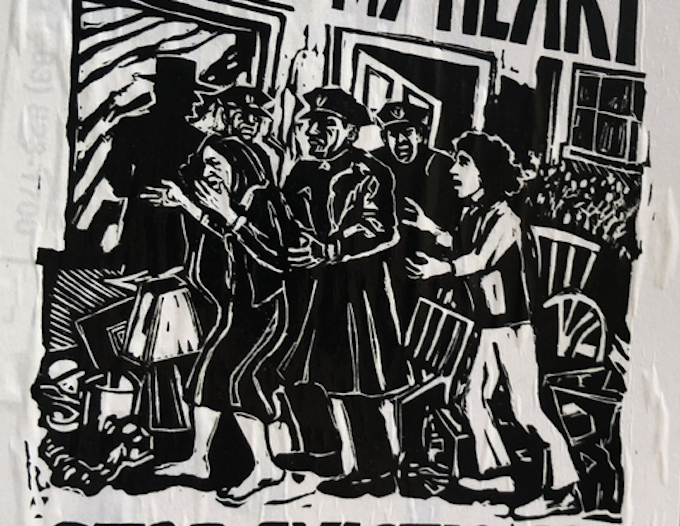

The boat metaphor is particularly interesting in the case of refugees; millions of them have desperately tried to escape the infernos of war and poverty in rickety boats and dinghies, hoping to get across from their stricken regions to safer places.

Sadly familiar sight

This sight has sadly grown familiar in recent years not only throughout the Mediterranean Sea but also in other bodies of water around the world, especially in Burma, where hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have tried to escape their ongoing genocide. Thousands of them have drowned in the Bay of Bengal.

The covid-19 pandemic has accentuated and, in fact, accelerated the sharp inequalities that exist in every society individually, and the world at large. According to a June 2020 study conducted in the United States by the Brookings Institute, the number of deaths as a result of the disease reflects a clear racial logic.

Many indicators included in the study leave no doubt that racism is a central factor in the life cycle of covid.

For example, among those aged between 45 and 54 years, “Black and Hispanic/Latino death rates are at least six times higher than for whites”. Although whites make up 62 percent of the US population of that specific age group, only 22 percent of the total deaths were white.

Black and Latino communities were the most devastated.

According to this and other studies, the main assumption behind the discrepancy of infection and death rates resulting from covid among various racial groups in the US is poverty which is, itself, an expression of racial inequality. The poor have no, or limited, access to proper healthcare. For the rich, this factor is of little relevance.

Moreover, poor communities tend to work in low-paying jobs in the service sector, where social distancing is nearly impossible. With little government support to help them survive the lockdowns, they do everything within their power to provide for their children, only to be infected by the virus or, worse, die.

Iniquity expected to continue

This iniquity is expected to continue even in the way that the vaccines are made available. While several Western nations have either launched or scheduled their vaccination campaigns, the poorest nations on earth are expected to wait for a long time before life-saving vaccines are made available.

In 67 poor or developing countries located mostly in Africa and the Southern hemisphere, only one out of ten individuals will likely receive the vaccine by the end of 2020, the Fortune Magazine website reported.

The disturbing report cited a study conducted by a humanitarian and rights coalition, the People’s Vaccine Alliance (PVA), which includes Oxfam and Amnesty International.

If there is such a thing as a strategy at this point, it is the deplorable “hoarding” of the vaccine by rich nations.

Dr Mohga Kamal-Yanni of the PVA put this realisation into perspective when she said that “rich countries have enough doses to vaccinate everyone nearly three times over, while poor countries don’t even have enough to reach health workers and people at risk”.

So much for the numerous conferences touting the need for a “global response” to the disease.

But it does not have to be this way.

While it is likely that class, race and gender inequalities will continue to ravage human societies after the pandemic, as they did before, it is also possible for governments to use this collective tragedy as an opportunity to bridge the inequality gap, even if just a little, as a starting point to imagine a more equitable future for all of us.

Poor, dark-skinned people should not be made to die when their lives can be saved by a simple vaccine, which is available in abundance.

Dr Ramzy Baroud is a journalist and the editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of five books. His latest is “These Chains Will Be Broken: Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons” (Clarity Press, Atlanta). Dr Baroud is a non-resident senior research fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA), Istanbul Zaim University (IZU). This article is republished with permission. His website is www.ramzybaroud.net