REWIND: By Crispin Maslog

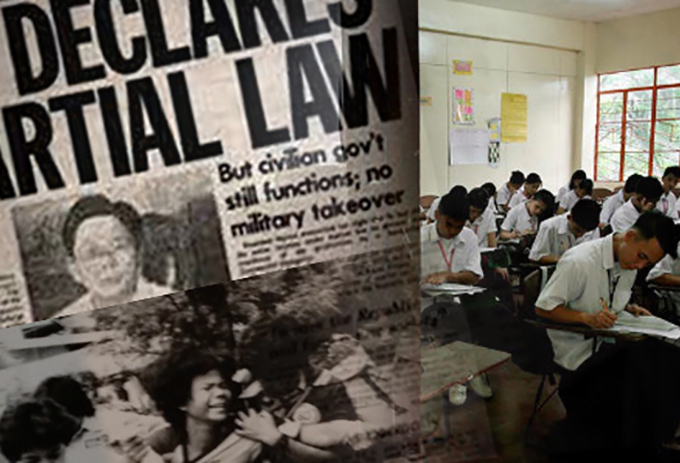

Filipinos under 48 today were not yet born when Martial Law was imposed on the Philippines by the late and unlamented dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos in 1972. But even to senior citizens like me, the memories are still crystal clear.

I was living in the province at that time, teaching journalism at Silliman University, Dumaguete City, the first journalism school outside Metro Manila.

I recall vividly that historic day Martial Law was announced – September 23, 1972, a Saturday. Dumaguete City woke up early as usual, expecting another of those unruffled, unhurried mornings that this “City of Gentle People” was famous for.

READ MORE: Breaking the news: Silencing the media under Martial Law

Then the six o’clock newscast over DYSR, the popular local radio station at that time located on campus, that hit like a thunderbolt: Martial Law Declared!

This was also the headline that Saturday morning of the local newspaper which my journalism faculty and I published, The Negros Express.

In the face of “anarchy and dissident threat to the existence of the Republic,” according to the newscast, President Ferdinand Marcos had declared martial law on September 21, for the first time in history. But Marcos had delayed the announcement by two days to give him time to round up the opposition leaders and prominent journalists.

Silliman University, thanks to DYSR, got the news ahead of the people in Manila and most parts of the country. DYSR was able to monitor Radio Australia which got its information from one of the international wire agencies in Manila before they were closed down by the military and before DYSR itself was closed down later that day.

Manila mass media were silent

On the morning DYSR monitored the Radio Australia newscast on martial law, the Manila mass media were silent. It was only towards noon that the government radio and television stations in Manila—the Voice of the Philippines (VOP, operated by the National Media Production Centre) and the stations of the Philippine Broadcasting Service—went on air with President Marcos’ Proclamation 1081, read by then Information Secretary Francisco Tatad.

The country was in a state of shock that day, ears glued to radio sets. Shock and disbelief later gave way to fear, as people heard over DZPI and VOP that hundreds of political leaders—led by Liberal Party Senators Benigno Aquino and Jose Diokno, Manila Times publisher Joaquin “Chino” Roces, Manila Chronicle publisher Eugenio Lopez Jr., and Philippines Free Press publisher Teodoro M. Locsin Jr.—were arrested.

When Martial Law was announced on September 23, some faculty members and many students of Dumaguete schools, majority from Silliman, were rounded up by the local Philippine Constabulary (PC) for interrogation and detention. Silliman University offices, like the School of Journalism and Communications and the office of the student paper, the Weekly Sillimanian, were raided by the Philippine Constabulary.

I remember that day very well. Shortly after the announcement, a group of PC officers came to my office, the School of Journalism. My secretary, face ashen white, came to my inner office to say, “Sir, the PC are here.”

I asked the officers what they were looking for. They did not look like they knew, but they were polite, opened a couple of cabinets and left promptly.

The following day, Sunday, the military knocked at the door of the Negros Express editor, Roberto Pontenila. They brought him to the PC stockade. Aside from Pontenila, two faculty and staff members and some 40 students (one of them Dionisio Baseleres, editor of the student paper, ended up in detention for one to six months, no charges filed.

All schools, including Silliman, were closed effective September 23, 1972, and nobody knew when they were going to reopen, if at all. The next few days were tense. No one in Silliman felt safe as the PC continued to pick up people for questioning, and to raid offices for presence of alleged subversive literature.

Students went into hiding

Students went into hiding and faculty and staff were burning whatever books and materials they had that only faintly smelled of subversion. The campus and the city were deathly quiet.

On October 14, President Marcos authorised all schools to reopen except the now infamous four—University of the Philippines units (including its Institute of Mass Communication), the Philippine College of Commerce, the Philippine Science High School and Silliman University.

UP was the centre of student activism in the Philippines. At the height of student activism, the UP activists barricaded the campus and set up a “Diliman Republic” that defied the Metropolitan Police for days.

The president of Philippine College of Commerce (PCC), Dr Nemesio Prudente, was noted for his staunchly nationalistic and radical political views and himself led student activism in his school. The Philippine Science High School was an acknowledged hotbed of activism.

Silliman campus activism had caught the attention of Malacanang Palace no less. President Ferdinand Marcos himself “scolded the university during a speech in Dumaguete, noting that members of the opposition, including Senator Jovito Salonga, Juan Liwag and Benigno Aquino Jr. were invited to speak on campus.”

He warned Silliman University, “do not engage in partisan politics because you are supposed to be an academic institution. You may regret it.”

Did we ever regret it.

‘The plunder of the nation’

“The plunder of the nation began the moment martial law was declared. Unprecedented looting of the country’s natural resources and wealth ensued. Marcos and his cronies exerted a vise over the national economy until it came under their total control. . . Every major economic activity was controlled by the First Family, their relatives, or cronies. This was the start of crony capitalism,” according to Ricardo Manapat in his meticulously researched 615-page book, Some Are Smarter Than Others (1991).

Award-winning American journalist Sterling Seagrave in another well researched 485-page book in 1988, The Marcos Dynasty, added: “Under Martial Law, the Philippines entered a grim period of human rights abuses. A new term, salvaging, came into use to cover the torture, disappearance, and death of ordinary citizens …

“Many of the horror stories were independently corroborated by diplomats, journalists, priests, scholars and international organisations such as Amnesty International. They are a litany of sadism, of dead rats being stuffed in mouths, of electric cattle prods jammed into vaginas, of mashed testicles, and prisoners being forced to eat their own ears.”

So on September 21, we celebrate the 48th anniversary of Martial Law, which the Marcoses would rather forget. But I cannot forget and I hope that the Filipino people will not forget, because he who does not remember his past is condemned to repeat it.

Dr Crispin Maslog is a former journalist with Agence France-Presse and retired journalism professor from Silliman University and UP Los Baños. He is also chair of the board of the Asian Media and Information Centre (AMIC), a research associate of the Pacific Media Centre and on the editorial board of Pacific Journalism Review.