SPECIAL REPORT: By Selwyn Manning

Warning: This story discusses details of the 15 March 2019 Christchurch mosque massacre.

At what point in time does an atrocity have a beginning? Is it when the first gunshot is fired? When the first victim is killed? When a killer first submits to thoughts of hatred, alienation, blame and decides to apply those emotions into physical action? Or, is it when racism is justified, when killing is considered defensible by those in whom one chooses to associate with, to support, to impress? Is it when one subscribes to another’s ideology of hate? Or when silence is a protector – chosen by reasonable people – when those around us speak of inhuman things?

“Ok lads, enough talking, it’s time for action.” With those words early on 15 March 2019, and expressed to his dark-net acquaintances, Brenton Harrison Tarrant initiated his plan to murder as many people of the Muslim faith as was possible.

Tarrant then packed six firearms into his vehicle, including two military-styled assault rifles (AR-15 .223 calibre) and semi-automatic shotguns. He added 7000 rounds of ammunition, a bayonet-styled knife, and four IEDs (improvised explosive devices).

Wrapped within a bulletproof-vest he reversed from the driveway of his rented Dunedin home and self-drove 361km northward to New Zealand’s largest South Island city, Christchurch.

Reconnaissance

Christchurch is known for its gardens, parks, sport, English-Victorian-styled architecture, earthquakes, parochialism, a modest inter-faith Muslim community; and, paradoxically, its white extremist gangs.

Two months earlier, in January 2019, Tarrant visited Christchurch. The purpose: reconnaissance of Al Noor Mosque – a place of prayer and worship for hundreds of the city’s Muslim people.

In January, Tarrant parked his vehicle adjacent to Al Noor Mosque, unpacked a drone and flew it above and over the facility. He recorded an aerial view video of the grounds, noting points of entry, exits, corridors where people could escape, where they could hide.

Tarrant observed how hundreds of people would attend Friday prayers. He decided Al Noor was the location, and, Friday was to be the day of the week which provided him an opportunity to kill as many people as possible on one single afternoon.

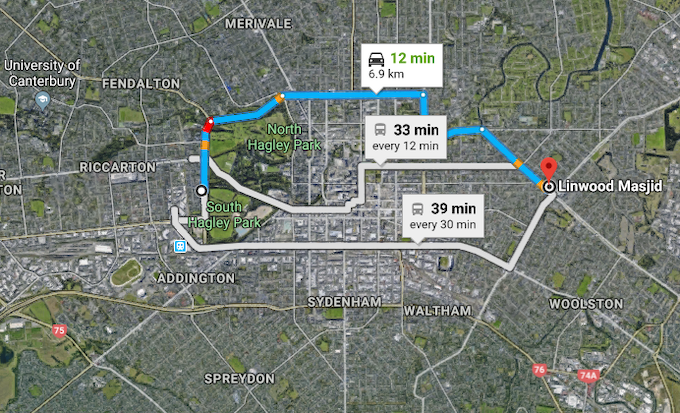

Christchurch is also a city built on a plane. Geographically it rests on a flat ancient seabed – framed only by the Port Hills to the south and the towering Southern Alps to the west. The city’s traffic is characteristically light (compared to other cities) and the route from Al Noor Mosque to nearby Linwood Islamic Centre is a short drive. Tarrant fathomed that even with news of a mass killer in the area, traffic would most likely be light.

Tarrant quietly, and unobserved, took notes. Once satisfied, he returned to Dunedin where he determinedly, and with precision, planned mass murder.

At no time during the reconnaissance, nor the planning phase, did New Zealand police nor Australia’s police, the Security Intelligence Services, the New Zealand Government Communications Security Bureau notice what was being planned and expressed online. Brenton Tarrant’s intensifying hatred grew, undeterred, against those who were not white. As is the case of many Western nations, New Zealand, along with its Five Eyes intelligence partners, Australia, Canada, Britain and the United States of America, had appeared more preoccupied with surveillance of those of Muslim and Islamic origins than they were of disarming an intensifying white extremist threat.

Alpha and Omega

In the early afternoon of 15 March 2019, Tarrant arrived at his first waypoint. He parked his vehicle in a neighbouring driveway. Around 190 worshippers (children, women, men) had already arrived at Al Noor Mosque and others were still making their way there for Friday Prayers.

It was a warm late Summers day. In a nearby park, people were playing. School children were enjoying the peace and fun that the garden city offered.

Inside his vehicle, Tarrant strapped his bulletproof vest tightly to his body. He put on a helmet. Earlier, he had fixed a video camera and a strobe light to the helmet – the latter was designed to confuse his intended victims; the camera was connected to the internet via a cellphone device so as to provide Tarrant the opportunity to livestream his intended atrocity to a Facebook audience.

Tarrant then sent a “Manifesto” to a white extremist website. He also emailed his intentions (with Manifesto attached) to the New Zealand Government, to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, and to national and international media.

Minutes later, Tarrant weaponed up, stepping from his vehicle he carried two semi-automatic firearms (including a shotgun) with multiple magazines, and approached the entrance to Al Noor Mosque.

“At that time four worshippers, Mounir Soliman, Syed Ali, Amjad Hamid and Hussein Moustafa, were at the mosque’s front entrance. Without warning you discharged the shotgun multiple times in quick succession, killing each of them. A wounded Mr Moustafa was despatched by you at point-blank range with shots to his back and head.” [New Zealand High Court ruling, Justice Mander, August 27, 2020].

That was just the beginning, the moment Brenton Tarrant decided to open fire, ultimately putting his plan into action. His hateful journey, once conceived in his past, had been nurtured by those with whom he chose to associate with. His racist views had become darker by the month. His decision to become a mass murderer, a terrorist by his own definition and admission, was now a reality.

Catharsis from horror

Throughout the week of August 24-27, New Zealanders discovered how detailed Tarrant’s plan was. There was a risk, due to Tarrant’s guilty plea (lodged some months earlier) and his decision to refuse legal assistance, that details of his crimes – forensically applied to a timeline by detectives, scientists and prosecutors – would be sealed beyond the reach and rightful consideration of survivors. New Zealanders of all ethnicities, colour and religions too, needed to hear detail of how this monstrous act of terrorism could have occurred in this relatively peaceful land.

Officially, the High Court summarised the charges:

“The Offender pleaded guilty to 51 charges of murder, 40 of attempted murder and one of committing a terrorist act after shooting worshippers at two mosques in Christchurch. Court held that no minimum period of imprisonment would be sufficient to satisfy the purpose of sentencing. Offender sentenced to life imprisonment without parole under s 103 (2A) Sentencing Act 2002.”

There was also a concern, that Tarrant, who had the legal right to address the High Court, would use that opportunity to express his white extremist ideology. As a preventive measure, the High Court’s Justice Mander applied tight controls on media, and insisted Tarrant would be withdrawn from the Court should he begin such a tirade.

Victims and survivors were offered the right to speak their impact statements to the court and, significantly to tell Tarrant what they thought of him, and of the true consequences his actions had had on their lives.

Initially, 60 people wished to read their statements to the court and to the killer. Others, after observing how their fellow Muslims accounts somehow were beneficial, also wished to have their experiences told.

Some spoke of how Tarrant had failed in his purpose, as their faith had strengthened since the murders, that they as a community had become stronger, and how loved they had felt when New Zealanders of all colours embraced them as valued members of the nation’s family. A common account reiterated how ‘you sought to divide us, to alienate us. You failed’.

While in court, Tarrant’s deportment was passive, absolutely. Whenever he was ushered into the court, his hands and legs bound in shackles, he was assisted by officers to sit before the packed public gallery. When the judge addressed him, he was respectfully at full attention. When addressed by his victims’ loved ones and survivors, he was attentive, although without emotion.

At one point, a murdered victims’ mother addressed Tarrant. She stated she had “no hate for him” as a person, that she forgave him. Tarrant acknowledged her with a nod. Began to blink rapidly and appeared to wipe a tear from his eye. Shortly after, New Zealanders learned that the killer had withdrawn his intention to address the court.

A total of 98 victims and loved ones read their impact statements to the court and to Tarrant. Some expressing distress and some anger. The killer was referred to as a “coward” by a school teacher, whose brother was murdered in cold blood. Another man, the son of a middle aged worshipper addressed Tarrant as a “maggot”. Another, that Tarrant was nothing but “rotten meat” to him. Three men concluded their account with a Muslim prayer and chanted Allahu Akbar while pointing defiantly at Tarrant.

The court observed in silence, noting the tragic recount of events told by those who suffer injuries from the bullet, the experience leaving physical, mental, emotional, social wounds as a consequence of Tarrant’s crimes – but none expressed a loss of faith in Islam nor of New Zealand as a community.

As Radio New Zealand reports: “One survivor, Dr Hamimah Tuyan left her two sons in Singapore to travel to the High Court in Christchurch to speak and honour her late husband, Zekeriya – the 51st victim to die.”

She told Radio New Zealand’s Morning Report she wrestled for some time if she should write a statement. Once she came back to Christchurch she decided she would listen to every victim statement delivered in court: “I was just so inspired by the brave brothers and sisters – their words, their feelings. I’m just so glad that I actually wrote it and opted to read it. That was the only way I could represent my husband and my boys,” she said on live radio.

Dr Hamimah Tuyan said she felt a weight lift from her shoulders and then left everything in the hands of God and the judge.

“We were all calm after the last session and basically waited … listening to each and every word of Judge Mander’s sentence until the end – two hours.” [Radio New Zealand].

She, and many others, spoke of catharsis in having had the courage to speak of their experience and their strength, and of the bravery of their loved ones who died on 15 March 2019.

Cold blooded reality

Then came the judge’s ruling. For four hours, Justice Mander read a precise account of what happened that day. In a move that was welcomed by the victims and New Zealanders, Justice Mander spoke of each victim and of their character, of the circumstances of how each person died.

For the first time, New Zealanders learned of the cold blooded reality of the consequences of hate that tore at the heart of the Muslim community that day.

Accounts like:

“As you made your way down the hallway of the mosque to the main prayer area, you shot Ata Mohammad Ata Elayyan and Ali Elmadani, murdering both men. You then entered the main prayer room at the rear of the building. There were over 120 worshippers present. They had heard the gunfire. Appreciating that something was very wrong, they moved to each side of the large open prayer area to where there were single exits in each corner.

“When you entered the main prayer room you initially fired at worshippers who were lying on the ground. You shot Ziyaad Shah. You then turned to the two large groups gathered on each side of the prayer area. There was little chance of escape. You fired your semi-automatic firearm into the mass of people on one side of the room. The rate of fire was extremely rapid. You repeatedly moved your weapon across that side of the room before turning to the other group of trapped people on the opposite side.

“As you turned your semi-automatic weapon on these worshippers, Naeem Rashid ran at you. Despite being shot, he crashed into you, forcing you down on one knee and dislodging a magazine from your vest. Mr Rashid had been hit in the shoulder and, as he lay on his back, you fired further shots at him. Mr Rashid died but his bravery allowed a number of his fellow worshippers to escape.

“By this stage you had emptied a 60-round magazine. You replaced that with another. Standing in the middle of the room, you fired rapid bursts towards each side of the prayer room where people were trying to hide or were attempting to escape. After reloading yet again, you continued to shoot at persons lying prone or trying to escape. You discharged rapid bursts across both sides of the room before approaching individual victims and shooting them. As Ashraf Ragheb sought to escape from a side room down the hallway to the main entrance, you shot and killed him. Already there were many dead.

“You moved closer to each now piled group of people lying deceased, wounded or feigning death on each side of the main prayer room. Worshippers, who were either crying out for help or who appeared to be alive, were systematically shot in the head. One of those was a three-year-old child, Mucaad Ibrahim. He was clinging to his father’s leg and you murdered him with two aimed shots.”

The judge continued, detailing how Brenton Tarrant then made his way outside Al Noor Mosque.

“Outside you shot at people attempting to flee. You shot Mohammad Faruk in the back, killing him. Wasseim Daragmih and his four-year-old daughter received life-threatening wounds. You fired in the opposite direction, hitting Sazada Akhter in the spine. She will be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of her life.

“Tarrant then returned to his vehicle. Quickly he rearmed himself with an assault rifle fitted with two 40 round magazines.

“You fired this weapon down a side driveway towards the back of the Mosque, murdering Muse Awale and Hamza Alhaj Mustafa, a 16-year-old boy who had escaped from the main prayer room and was sheltering behind vehicles. Another man, Mohammad Shamim Siddiqui, was critically wounded.

“You then returned to the main prayer room. As you entered you saw Md Hoq, who was wounded,sitting up against a window. You aimed one shot at Mr Hoq, killing him instantly, before firing further shots at a group of people lying in one corner. There were some 30 deceased or critically wounded worshippers in this mass of people. You delivered fatal shots to those who were still alive.

“You then reloaded your weapon and walked over to the group of people lying in the opposite corner and fired into them. You noticed Haji Nabi attempting to shelter behind a small wall. With two carefully aimed shots you murdered Mr Nabi before walking to within a metre of the piled group and firing further shots into those who were either deceased or mortally wounded. Any persons who showed signs of life were shot.”

The judge’s ruling continued on, every precise detail that the police, scientists, and prosecutors had discovered was read to Tarrant. The killer’s gaze remained attentive. Silently, he sat, emotionless, listening to every word.

Observers reflected on how Brenton Tarrant appeared a hollow shell of a human being. Immediately after his arrest, Tarrant presented as arrogant, remorseless, complaining to police that he was disappointed that he didn’t kill more people. He was then in peak physical condition, clearly having been working out regularly. But this week, he appeared without emotion, without purpose, passively listening to the accounts of victims and that of the judge detailing the facts of what he had done. He did not challenge the facts, rather he had accepted them as accurate, a true account of his crimes.

Justice Mander continued:

“After exiting the mosque for the second time you saw two women attempting to escape. You shot Ansi Karippakulam Alibava and Husna Ahmed. Ms Ahmed was killed. Ms Karippakulam Alibava was wounded. While she lay on the street, pleading for help, you murdered this defenceless young woman, firing two shots at her from point-blank range. You then returned to your vehicle and inflicted the indignity of driving over her body as she lay in front of the driveway from which you exited.”

Still, Tarrant remained emotionless, leaving some to ponder whether he was intent to create an enigma of himself, a mysterious figure who refused to offer any words or emotion upon which others may define him. Rather, he had earlier defined himself to appointed psychiatrists and psychologists as a “terrorist” and a “fascist”. He had stated to the clinicians, appointed to assess his personality and condition, that in the months leading up to the killings, he had sunken into despair, into a depression. That he was angry at the world and wanted to hurt it, damage it.

The child, the man:

Radio New Zealand investigated Brenton Tarrant’s background. The following segment is a paraphrase of that investigation.

Brenton Tarrant’s life experience was unremarkable, at least in the beginning. He was born on October 27, 1990 and raised in rural Australia, in a town called Grafton some 500km north of Sydney. He was the youngest of three siblings. His parents separated while he was still at school. He played sport (rugby league) but was overweight and was bullied, to a degree, by others of his age. His father worked as a rubbish collector, and his family was respected in the general Clarence Valley area.

One of Tarrant’s cousins told Australia’s 7News, there was little in his background that would have indicated problems ahead. But, when his father died of cancer when Tarrant was 20 years of age, he was crushed by the loss. He inherited A$500,000 from his fathers estate. Dabbled in investments. Then travelled extensively. It was during his overseas experience abroad, particularly in Europe, that he was radicalised.

Details are vague, but court accounts place him in France where he was attracted to white extremist groups with which he increasingly shared commonly held racist views. He continued to travel around Europe, and developed an interest in the countries that were once ruled by the Ottoman Empire, visiting historic battle sites. He travelled through greater Asia, visiting Pakistan and the border areas of Afghanistan.

Then, in August 2017 he emigrated to Dunedin, New Zealand. He joined a rifle club, acquired a firearms licence from the New Zealand Police, and joined a South Dunedin gym.

He kept largely to himself, isolating his ideas, his anger, his purpose from those around him.

Brenton Tarrant never sought to work in New Zealand and showed no intention to get a job.

Wider family members visited Tarrant while he lived in Dunedin. They returned to Australia, noting concerns to his immediate family that he was not in a good state of mind, and had shown them that he had many guns.

Then, as Radio New Zealand reported, Tarrant’s last message to the white extremist group on 8Chan came on 15 March 2019:

“’It’s been a long ride and … you are all top blokes and the best bunch of cobbers a man could ask for,”’Tarrant posted.

“Radio New Zealand noted: ‘His friends were faceless, his interactions existent only in cyberspace.’” [Radio New Zealand]

The courtroom account continued

Justice Mander:

“As you drove away from the Al Noor Mosque you continued to shoot at anyone who you considered should be the target of your hate. You discharged a shotgun at two men who appeared to be of African descent. A short distance on you saw Muhammad Nasir and his son walking towards the mosque dressed in traditional clothing. You again discharged the shotgun, seriously wounding Mr Nasir, before actioning the weapon again and pointing it directly at the boy who was trying to hide behind a wall. You pulled the trigger but it failed to fire.

“You then sped away, driving directly to the Linwood Islamic Centre. On the way you came abreast of another vehicle being driven by a Fijian man. You pointed your shotgun at him. Despite repeated attempts to discharge the shotgun it failed to fire.

“When you got to Linwood you approached the mosque on foot down a long driveway, armed with yet another firearm. You saw three people in and around a car. You shot Ghulam Hussain in the head, killing him, before firing at and wounding Muhammad Raza, who had got out of the other side of the vehicle. You shot another occupant of the car, Karam Bibi, before advancing up the driveway, where you saw Mr Raza attempting to find cover behind a fence. He attempted to retreat from you. Despite his pleas to spare him, you murdered him. A wounded Ms Bibi sought to hide in front of the vehicle. You walked to within metres of her as she lay prone with her head buried in her hands, stood over her, and killed her.”

Tarrant approached the mosque, passing a window. He saw a silhouette of a man. He shot him with a single shot to the head. The man’s name was Mohammed Khan.

With your weapon now empty, you ran down the driveway back to your vehicle. As you reached the car, Abdul Aziz Wahabazadah, who had courageously followed you down the driveway, challenged you. You retrieved another semi-automatic rifle from your vehicle and fired at him. He dived between some parked cars, before you walked back up the driveway to the main entrance to the mosque.

[Selwyn Manning’s author’s note: I wrote about this moment, in the German magazine Cicero.de in March 2019, shortly after the murders:]

“Inside Linwood Mosque was Abdul Aziz, a man who had gathered with his Muslim brothers. He had just begun his second prayer when he heard gunshots outside. At first he thought it was someone playing with firecrackers (fireworks). But then, within seconds, he heard people screaming.

“Mr Aziz picked up an EFTPOS (electronic funds transaction) machine from a table inside the mosque. He ran outside. He saw a man he describes as looking like a soldier. He said to the man: ‘Who are you?’ Mr Aziz then saw three people lying on the ground dead from shotgun blasts. He realised the man was the killer. He approached the attacker, threw the EFTPOS machine, hitting the killer, who in turn took from his vehicle a second firearm (a military style semi-automatic assault rifle) and fired four to five shots at Abdul Aziz, missing him. Then, in an attempt to lure the killer away from other people, Mr Aziz shouted at the killer from behind a car: ‘Come, I’m here. Come I’m here!’

“Mr Aziz said he didn’t want the killer to go inside the mosque and kill more people. But the killer remained focused. He walked directly to the entrance, once inside the mosque he continued his killing spree. Survivors speak of the killer wearing ‘army clothes’, dressed in ‘SWAT combat clothing’, helmeted, wearing a vest and a balaclava… Written on the rifle were the words, ‘Welcome to hell’.” [Attentat in Christchurch – Willkommen in der Hölle]

In the High Court this week, Justice Mander continued:

“There were several people standing inside the entranceway and further into the building at whom you repeatedly fired. You killed Musa Patel. Walking further into the mosque, you shot and killed Linda Armstrong. People were huddled in corners of the room or trying to escape as you fired your weapon, killing Mohamad Mohamedhosen. You continued to fire the semi-automatic rifle until it ran out of ammunition, at which point you dropped it and ran back to your vehicle.

“Mr Wahabazadah chased you down the driveway, yelling at you. You removed the bayonet from your vest but retreated in the face of his advance. As you began driving away, Mr Wahabazadah got close enough to throw one of your discarded weapons at your vehicle.

“After leaving the Linwood Mosque, your intention was to drive to Ashburton to attack another mosque, but your vehicle was rammed off the road by a police car and you were apprehended by two armed police officers. You were anxious not to be shot and offered no resistance,” Justice Mander read.

The judge then spoke about the character of each of those who were murdered, about people like:

“Haji Mohemmed Daoud Nabi was a 71-year-old who had been married to his wife for 46 years. He was a role model and leader to his family; a best friend to his children and to his wife. For them the pain and anguish never goes away. Mrs Nabi describes herself as ‘alive, but not living’.”

And…

“Ansi Karippakulam Alibava’s husband found her lying on the road. He sat down beside her until police told him it was not safe. He knew when ambulance staff were not treating her that she had died. He is devastated. He finds himself constantly reminded of the events of that day and the loss of his dear wife. He can find no solace.”

And…

“Ozair Kadir was training to be an airline pilot like his big brother. His death has left a scar on the hearts of his proud parents. His murder haunts his father.”

And…

“Sayyad Ahmad Milne was a precious 14-year-old boy with his whole life before him. His murder has left a huge hole in his parents’ hearts. Despite his father’s resilience and forgiveness, they grieve for him deeply.”

And… …

“Mucaad Aden Ibrahim was younger still — a three-year-old infant. His father described him as ‘the happiness of the household’ — a vibrant young boy who made friends with everyone he met. No family can recover from the murder of such a small child.”

In the end, Justice Mander considered what sentence is permitted under New Zealand law. As a liberal social democratic country, New Zealand repealed the death penalty for murder at the end of the 1950s.

After consideration, the judge sentenced Brenton Harrison Tarrant to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole – which means, he will die in prison. This is the first time any accused has received this sentence in New Zealand.

Officially, the judge delivered his order:

“On each of the 51 charges of murder (charges 1-51) you are sentenced to life imprisonment. I order that you serve the sentences without parole.

“On each of the 40 charges of attempted murder (charges 52-91) you are sentenced to concurrent terms of 12 years’ imprisonment.

“On the charge of committing a terrorist act (charge 92) you are sentenced to life imprisonment.

“I also direct that the four psychiatric and psychological reports prepared for this proceeding be made available to the Department of Corrections.”

And then came the judge’s final order:

“Stand down.”

On writing this account, I am mindful that we cannot republish a summary of each of the victims when 91 people have been either killed or maimed by one man’s actions. It feels terribly selective when choosing who to include, and who to exclude from this report. How can one apply news values to people who have had their present and future stolen from them? One cannot.

Therefore, I encourage you, readers, to read the unabridged ruling from the New Zealand High Court. While upsetting, it will offer a sober account of what occurs when hatred is left to grow inside us, when others do not know how to react or challenge when hatred is expressed: https://www.courtsofnz.govt.nz/assets/cases/R-v-Tarrant-sentencing-remarks-20200827.pdf

Also, there is this awful thing, this contemplation, this series of unanswered questions which remain after the killing ceases, well after the victims’ faces become one. Answers remain elusive even after the verdict is read, the sentence is delivered, and the survivors have been ushered home to pick up the pieces of their lives. We are left to wonder, why? That question, that one word, will haunt us for the rest of our days.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s reaction

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern:

“I want to acknowledge the strength of our Muslim community who shared their words in court over the past few days.

“You relived the horrific events of March 15 to chronicle what happened that day and the pain it has left behind.

“Nothing will take the pain away but I hope you felt the arms of New Zealand around you through this whole process, and I hope you continue to feel that through all the days that follow.

“The trauma of March 15 is not easily healed but today I hope is the last where we have any cause to hear or utter the name of the terrorist behind it. His deserves to be a lifetime of complete and utter silence.”

Alpha and Omega, as we began, so we close

At what point in time does an atrocity have a beginning? Is it when the first gunshot is fired? When the first victim is killed? When a killer first submits to thoughts of hatred, alienation, blame and decides to apply those emotions into physical action? Or, is it when racism is justified, when killing is considered defensible by those in whom one chooses to associate with, to support, to impress? Is it when one subscribes to another’s ideology of hate? Or when silence is a protector – chosen by reasonable people – when those around us speak of inhuman things?

Selwyn Manning is editor of Evening Report. A German language version of this article was published by Cicero.de magazine in Germany. We also invite you to view this week’s episode of A View from Afar with Paul Buchanan and Selwyn Manning where they discuss, in depth, the causes, impact and possible solutions when dealing with white extremism.