Selwyn Manning, editor of Evening Report, profiles the Christchurch atrocity that has outraged and shaken a peaceful South Pacific nation.

Out of the blue:

It was 1:39pm, Friday March 15. As was usual for a Friday, hundreds of people had turned up to pray at the Al Noor Mosque in Riccarton, Christchurch. All was peaceful, women, children, men, people of all ages young and old, both Sunni and Shia, were in contemplative repose free of worry.

It was a mild, late summer, 20 degrees Celsius day. Earlier, the touring Bangladesh cricket team had briefly visited the mosque, but left early to attend a press conference. By 1:39pm, they had returned and were outside exiting a bus, intending to continue with their prayers inside the mosque.

At 1:40pm, ahead of the team, a man entered the mosque walking quickly up the front steps. He was carrying an assault rifle and dressed in combat uniform. He immediately began shooting people who were kneeling in prayer.

The shots rang out and the Bangladesh team members realising they were witnesses to an attack, retreated, and fled on foot to nearby Hagley Park.

Back inside the Al Noor Mosque, scores of worshippers were being gunned down, some killed instantly, others bleeding to death. The victims included little Mucaad Ibrahim who was three years of age. Mucaad was known by his loved ones as a wise “old soul” and possessed an “intelligence beyond his years”.

Eye witnesses said that once the killer began shooting people, little Mucaad became separated from his family. In the chaos, his family could not find him. The next day police confirmed he too had been shot dead by the killer.

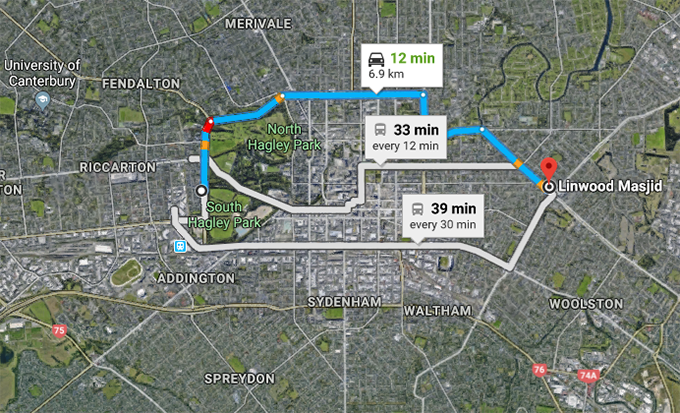

The murders continued at the Al Noor Mosque until the killer’s firearms ran out of bullets. Then, he simply walked out of the mosque, got in his car, and drove six kilometres to the Linwood Mosque. There too were people who had gathered for their regular Friday afternoon prayers.

Inside Linwood Mosque was Abdul Aziz, a man who had gathered with his Muslim brothers. He had just begun his second pray when he heard gunshots outside. At first he thought it was someone playing with firecrackers (fireworks). But then, within seconds, he heard people screaming.

Aziz picked up an EFTPOS (electronic funds transaction) machine from a table inside the mosque. He ran outside.

He saw a man he describes as looking like a soldier. He said to the man: “Who are you”. Mr Aziz then saw three people lying on the ground dead from shotgun blasts. He realised the man was the killer. He approached the attacker, threw the EFTPOS machine hitting the killer, who in turn took from his vehicle a second firearm (a military style semi-automatic assault rifle) and fired four to five shots at Abdul Aziz, missing him. Then, in an attempt to lure the killer away from other people, Aziz shouted at the killer from behind a car: “Come, I’m here. Come I’m here!”

Aziz said he didn’t want the killer to go inside the mosque and kill more people. But the killer remained focussed. He walked directly to the entrance, once inside the mosque he continued his killing spree. Survivors speak of the killer wearing “army clothes”, dressed in “SWAT combat clothing”, helmeted, wearing a vest and a balaclava.

Inside the Linwood Mosque, another witness, Shoaib Gani, was kneeling in prayer. He heard a noise like fireworks but he and others weren’t too concerned and continued with their prayers. Then, as he and his fellow worshipers were kneeling speaking verses from the Koran, the man next to him fell forward with blood pouring from his head. He had been shot and killed instantly, Gani said. Then others too began falling to the floor dead.

Gani crawled under a table. He saw the killer and his firearm. “Written on the rifle were the words, ‘Welcome to hell’,” he said.

Victims, who were wounded and bleeding, were pleading with Gani to help them. But he was frozen to a spot under a table knowing that the killer was walking around the mosque killing as many people as he could. Gani believed he too would also soon be dead, so he reached for his cellphone, he called his parent’s back home in India. But no one answered. He tried to call his father’s number, but the phone kept ringing. He saw people around him bleeding to death. Others with fatal head-wounds: “Their brains were hanging out. I just couldn’t do anything. I didn’t know what to do.” Gani phoned 111 (the New Zealand emergency number) and told the authorities people were dead and injured: “The lady on the phone asked me to stay on the line as long as I could.”

Outside, Abdul Aziz picked up one of the killer’s discarded shotguns. Inside the mosque, the killer’s assault rifle ran out of bullets. The killer then “dropped his firearm” and ran back to his vehicle. He got in the driver’s seat. Aziz then ran toward the car. He threw a discarded shotgun at the killer’s vehicle: “I threw it like an arrow. It shattered his window.” Aziz thinks the killer thought someone had shot at him with a loaded gun. The killer turned. He swore at Aziz. When the window burst it covered the inside of the car with glass. Aziz said the killer “then took off” driving in his car. He then turned right away from the mosque driving through a red traffic light and out into Christchurch suburban streets.

Some minutes later, police and ambulance officers arrived at Linwood Mosque. Anti-terrorist armed police entered the mosque. Inside, Gani said the survivors were ordered to put their hands up above their heads. The mass murder scene was covered in blood. The police then secured the area. Some victims survived because they were under the bodies of the dead. Police told survivors to gather near a grassed area outside. There, people began weeping for their husbands, wives, parents, children, friends.

The arrest:

Seventeen minutes later, two police officers identified the killer, apparently driving his car. They drove the police car into the killer’s vehicle, ramming it against a curb. Immediately, they disarmed the killer, cuffed him, and noticed home made bombs in the vehicle – IEDs (improvised explosive devices). They arrested the man and secured the scene.

The rest of Christchurch was in lockdown, children were kept safe inside their classrooms, hospitals began to prepare for casualties, the city’s streets became eerily quiet, people were locked in to libraries, shops, their homes. Police and armed forces helicopters networked the skies. No one knew if the terrorist attacks were committed by a group of people or a lone gunman.

But back inside and at the entrances to the two mosques, 50 people were dead – one of the dead was discovered the next day by police; the body was laying beneath others who had been killed. Scores of others were in hospital fighting for their lives, at least another 10 were in a critical condition in intensive care. Pathologists from all over New Zealand and Australia were heading to Christchurch to help with documenting the method of murder of the dead.

Within hours of the killings, Australian media named the alleged killer as an Australian-born citizen named Brenton Tarrant, 28 years of age. On Saturday morning The Australian newspaper’s front page read “Australia’s evil export”.

Other media in New Zealand followed with details of the man’s background. Brenton Harrison Tarrant appeared in court the next day charged with one single count of murder. Other charges will follow. His duty lawyer did not seek name suppression nor bail, the lawyer told the judge: “I’m simply seeking remand and a High Court next-available-hearing date.” Tarrant stood cuffed, smiling at those in the courtroom, at one point signaling with his fingers a “white supremacist” sign. He will next appear in the Christchurch High Court on April 5.

The aftermath:

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern later told media: “It was absolutely his [the offender’s) intention to continue with his attack.” PM Ardern said: “Police are working to build a picture of this tragic event. A complex and comprehensive investigation is (now) underway.” To balance the requirement of investigation with the customs of Muslim burials, PM Ardern said liaison officers were with the victims’ loved ones to help “in a way that is consistent with Muslim faith while taking into account these unprecedented circumstances and the obligations to the coroner”.

PM Ardern said survivors of the massacre had indicated that this attack was not “of the New Zealand that they know”.

One day later, survivor Shoaib Gani (mentioned above) told media he still could not sleep or eat. The sounds and sights were still vivid in his head: “I still can feel myself lying on the floor waiting for the bullets to hit me.” He said, he will travel back to India to visit family, but he will return to Christchurch: “It’s just a few people, you know. You can’t blame the whole of New Zealand for this… It’s a good country, people are peaceful. Everybody has helped me here. One right wing (person) doesn’t mean everyone is bad. So I can come back here and live and hope nothing like this happens in the future.”

In the hours after the attacks, all around New Zealand, in the cities and in small country areas, police were stationed and were ready in case others were involved and were preparing further crimes.

Beside the police officers, people, of all races and religions, began laying flowers at the steps to their local mosques. Messages included read: “Salam Alaikum, Peace be unto you”, and, “Aroha nui”, “Peace and love”, “You are one of us”. The outpouring of grief swept the South Pacific nation, and as this article was written, a mood of support, comfort, reassurance and solidarity with those of Muslim faith was in evidence.

In Australia, Sydney’s landmark Opera House was like a beacon in the night; coloured blue, red, and white – the colours of the New Zealand flag embossed with the silver fern (ponga) an emblem of Aotearoa New Zealand. Australia’s peoples, like in New Zealand, began laying flowers at the steps of its mosques in a gesture of inclusiveness.

In the aftermath, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has committed to ongoing financial assistance to dependents of those who have died or are injured, and assistance, she said, would be ongoing.

Questions are being leveled as to how a person with hate can enter, live, and purchase weapons in New Zealand while expressing hate toward other cultures and harbouring an intent to kill others.

PM Ardern said: “The guns used in this case appear to have been modified. That is a challenge police have been facing, and that is a challenge that we will look to address in changing our laws… We need to include the fact that modification of guns which can lead them to become essentially the kinds of weapons we have seen used in this terrorist act.”

When asked how she was coping personally with the tragedy, she said: “I am feeling the exact same emotions that every New Zealander is facing. Yes, I have the additional responsibility and weight of expressing the grief of all New Zealanders and I certainly feel that.”

That responsibility includes ensuring New Zealand’s police, the nation’s intelligence and security services and “the process around watch-lists, including whether or not our border protections are currently in a status that they should be, and, including our gun laws.”

The backstory:

Indeed, New Zealand is part of the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence network that includes the USA, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Global surveillance is coordinated and prioritised among the Five Eyes member states. While significant resource, technology and sophistication is committed to the Five Eyes intelligence agencies, New Zealanders fear that those who find themselves as targets, or within the scope of intelligence officers, are predominantly of the Muslim faith.

In contrast, the accused killer who allegedly committed the horrific Christchurch mosque attacks, has been active both on social media and the dark web expressing, with an intensifying degree, his ideology of hate and intolerance. It does appear of the highest public interest, certainly from an open source intelligence point of view, to ask questions of why New Zealand’s (and indeed the Five Eyes intelligence network’s) surveillance experts did not detect the expressed evil that had radicalised the heart and mind of the perpetrator of this massacre.

It is also fact that New Zealand is a comparatively safe and peaceful nation. But within its midst are people and groups fermenting on racially-based hate ideas. Whether it be in isolation or among organised groupings, the threat of racially driven terror crimes exists.

The alleged killer, Brenton Tarrant, has lived among those of New Zealand’s southern city Dunedin for at least two years. It appears he was radicalised around 2010 after his father died and he toured Europe. He wrote about becoming “increasingly disgusted” at immigrant communities. In early 2018, Tarrant joined a Dunedin gun club and began practising his shooting skills and allegedly planned his attacks.

Regarding Christchurch, while it has a history of overt white racist gangs, at this juncture, it does not appear they were directly involved in this series of crimes.

But this leads to many unanswered questions, including:

- Was the killer a lone mass murderer, a sleeper in a cell of one?

- Were those with whom he communicated and engaged with on the web in extreme white racist ideologies aware of his plans?

- Was Christchurch chosen by the killer for logistical reasons?

- Was it because the city is easier to drive around than Dunedin, Wellington or Auckland?

- Was it because Christchurch has at least two mosques within easy driving distance?

- Were the Bangladesh Cricket team in his scope of attacks?

- Was the killer attempting to incite a violent response from Christchurch’s burgeoning Muslim community, or, expecting a response from the Alt-Right, from white racist groups such as the Right Wing Resistance (RWR), the Fourth Reich, and Christchurch’s skinhead community?

The future:

Survivors of Friday 15th’s terrorist attack say they have complained of an increase in racism and expressed hate in recent times. They say, their concerns have not been taken seriously. These are the concerns that Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has committed to listen to, has committed to represent, and, as the prime advocate for her country’s peoples, to act on to ensure cracks in New Zealand’s border, security and intelligence apparatus are corrected.

And, what of New Zealand’s social culture? How will it be affected? That will be determined by the actions of each individual person, each community, town and city and how as a nation New Zealand redefines “The Kiwi Way”.

Members of New Zealand’s media will also need to act responsibly. It is fair to say some have a reputation for argument that verges on alt-right intolerance, for example, on Twitter only two days after the mass murders, a prominent radio journalist, who is employed by one of New Zealand’s largest networks, tweeted: “28 years on an [sic] we still haven’t stopped madmen getting guns. #ChChMosque… [Replying to @Politikwebsite] And the neo nationalist right are the result of the virtue signaling exclusionary left.”

Perhaps such examples are out of step with New Zealand’s population. But such attitudes do create a dialogue of justification for those who harbour intolerance. However, if the outpouring of love and compassion continues to bind rather than divide, then perhaps New Zealand has received, as they say, “a wake-up call”, where racial intolerance and extreme ideologies have no place among peoples of all kinds, Maori and Pakeha, of all religions, political persuasions and creeds.

One thing is certain; to stamp out the evil of hate extremism, New Zealanders will pay a price that will be charged against the Kiwi lifestyle. Personal liberties of freedom, of expression and privacy will certainly be eroded further as this nation of the South Pacific grapples with how to keep its people safe. The means of how to achieve relative safety will be hotly debated, but it is a necessary juncture in this nation’s history, a moment when we all must confront and challenge ourselves so that people of innocence, people like little three-year-old Mucaad Ibrahim, can go about their days in trust, in peace, in joyful purpose and achieve their deserved potential. Anything less is a second killing for the victims of Friday, 15th, New Zealand’s darkest hour.

Selwyn Manning is editor and publisher of Evening Report, a companion publication with Asia Pacific Report. He is also a former chair of the Pacific Media Centre Advisory Board. This article was originally published by the German magazine Cicero.de under the title: Attentat in Christchurch – Willkommen in der Hölle. It is republished here with permission.