By Dieqy Hasbi Widhana in Jakarta

Indonesia’s National Press Day (HPN), which falls on February 9 – yesterday, is a reminder of the murder of Radar Bali journalist Anak Agung Gede Prabangsa in 2009.

Based on the results of an investigation by the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI), which was later published under the title “The Bloody Trail After News“, Prabangsa was murdered because he wrote at least three articles on the manipulation of project budgets valued at around 40 billion rupiah (NZ$47 billion) in Bangli regency, Bali.

The three reports were titled, “Supervision after a Project is Running”, “Sharing the Bangli Education Office P1 Project” and “Agency Head’s Document Deemed Flawed”.

READ MORE: The Bloody Trail After News [Bahasa Indonesian]

The mastermind behind Prabangsa’s murder was Susrama, a contractor who routinely handled contract and procurement tenders for several government offices and agencies in Bangli, Bali.

Susrama is also the younger brother of Bangli Regent I Nengah Arnawa, who at the time was an Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) legislative candidate in the 2009 elections, and was then elected as a member of the Bangli Regional House of Representatives (DPRD). Susrama was subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment for Prabangsa’s murder.

The irony, however, is that Susrama’s life sentenced has been commuted by President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

Through a sentence remission contained in Presidential Decree Number 29/2018, Widodo reduced Susrama’s sentence from life to 20 years imprisonment. Susrama was the 94th in a list of 115 convicts who received sentence remissions.

Convict profiling

Legal Aid Institute for the Press (LBH Pers) executive director Ade Wahyudin says that the Susrama’s remission failed to consider a variety of aspects.

“What was missed in the convict profiling study, was what were the case details, the social effect of a case such as this”, Wahyudin told Tirto.

In the same vein as Wahyudin, AJI chairperson Abdul Manan said that Widodo’s decision was very disappointing because the remission given to Susrama completely ignored the public’s sense of justice.

On Friday afternoon, Wahyudin and Manan met with the Director-General for Correctional Institutions at the Ministry for Justice and Human Rights (Kemenkum HAM), Sri Puguh Budi Utami.

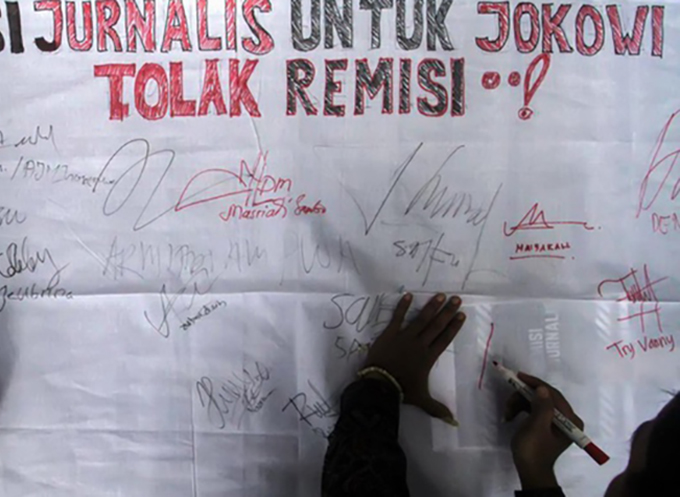

Accompanied by a representative from the Indonesian Legal Aid Institute (YLBHI), the two conveyed their complaints over the remission and handed over a petition put together by AJ, the LBH Pres and YLBHI.

“We asked that the remission for Prabangsa’s murder be revoked,” said Manan explaining the demands they took to the president.

Poor press freedom ranking

According to Manan, using the standards set by Paris-based global media freedom agency Reporters Without Borders, the state of press freedom in Indonesia is indeed very dim. Indonesia’s ranking is 124th out of 180 countries, lower even that Timor-Leste.

“It’s below 100, that’s in the underdog league, right. Categorised very bad,” said Manan.

Widodo has indeed routinely appeared at annual celebrations of National Press Day organised by the Indonesian Journalists Association (PWI). However, explained Manan, this has not automatically translated into efforts to strengthen press freedom in Indonesia.

“The February event commemorated by PWI was largely ceremonial. Totally inadequate to show that he sides [with journalists]”, he said.

There are many things that Widodo should be able to do rather than just taking part in ceremonial National Press Day commemorations. For example, said Manan, asking the Kemenkum HAM to look at the proposed revisions to the Criminal Code (KUHP), specifically the new on “contempt of court”.

The current formulation is problematic because journalists can be sentenced to five years jail if their journalistic work influences a judges’ verdict.

In addition to this, there is Article 494 on revealing confidential information. Likewise, Article 309 Paragraph (1) which has the potential for multiple interpretations and is susceptible to being used to criminalise journalists.

Articles too vague

“He should, if he wants to defend the press, [be able] to initiate the creation of regulations that support a climate of press freedom. Annul the articles which endanger the independence of the press because they are too vague,” he said.

The need to revise these problematic articles is becoming more urgent bearing in mind that in the last year there have been two efforts to criminalise journalists.

Those who have fallen victim were the former editor of Serat.id, Zakki Amali and Manan himself. The two were criminalised for investigating alleged plagiarism by Semarang State University (Unnes) rector Fathur Rokhman and the IndonesiaLeaks “red book” scandal allegedly involving National Police Chief (Kapolri) General Tito Karnavian.

“The Serat.id case was clearly just a press dispute. Police should be very careful in handling this. Ideally, pushing for the case not to be handled as a criminal case, so that it can be resolved though the mechanisms of the UU Pers (Press Law), namely by asking Unnes to submit a complaint with the Press Council”, explained Manan.

“Meanwhile the IndonesiaLeaks case is very clear cut and if they want to make an issue out of reports which were carried by five different media outlets, it’s inappropriate it to deal with it as a crime. The party that feels injured, if that’s Kapolri, should set an example by dealing with the case through mechanisms which are already provided for by the UU Pers”.

Still lots of homework

There is lots of homework that Widodo which needs to prioritise in order to protect press freedom in Indonesia.

Take for example his vision, mission and action program when he first ran as a presidential candidate in the 2014 presidential election. Widodo pledge to reorganise the ownership of broadcast frequencies in the hope of preventing monopolies by groups of people or broadcasting industry cartels.

According to doctoral research by Ros Tapsell from the Australian National University which was publish as a book titled “Media Power in Indonesia” (2017), there are eight media conglomerates that monopolise the public broadcast frequencies.

Aside from the problem of media conglomerates, Widodo also needs to fix the problem of the clearing house, a mechanism aimed at screening requests for permits by foreign journalists wanting to report on Papua.

The clearing house involves 19 working unit from 12 different ministries and is known for being convoluted and time consuming.

When he attended the great harvest in Marauke regency in Papua on May 10, 2015, Widodo asserted that these procedures would be abolished. Widodo declared that there should be a transparent mechanism with objective standards used to evaluate foreign journalist permit requests to report on Papua.

Journalists spied on

“Journalists find it difficult to obtain permits to report [on Papua], they are even spied on. In other cases their fixers are intimidated”, he said.

The other no less important problem is intimidation. Based AJI’s advocacy team’s records, during Widodo term in office new patterns of violence against journalists have emerged in the form of harassment and releasing private information through social media.

In 2018 there were three cases of journalists being persecuted in the online media. The victims were journalists from kumparan.com and detik.com. Their private data was publically released after they reported on the “211 Defend Islam Action” by a group who objected to the reports that they wrote.

“No legal action is ever taken in case journalists being persecuted. But, several cases of persecution where the victims were not journalists have been pursued legally. The president must show a clearer commitment to press freedom, particularly in its real application,” he said.

Wahyudin also raised the issue of poor protection for journalists under Widodo’s watch.

“There has been absolutely no progress. He’s been exactly same as the SBY [Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono] era, Jokowi. He hasn’t given attention to press freedom. Perhaps he thinks it’s already safe or resolved. Yet every year there are [incidents] of violence against journalists,” said Wahyudin.

Concrete steps

The government’s role, said Wahyudin, should be to guarantee that press freedom is protected. Yet Widodo has not fully realised this.

“It’s not enough. The government must take concrete steps in resolving murder cases. [Otherwise] the effect of ignoring cases of murder and valence will just be mushrooming impunity. Our democracy [itself] will become sick,” he said.

“In general terms, Widodo’s [new] vision and mission does not address press freedom. It more prioritises infrastructure but the aspect of civil freedoms are still very lacking.”

Translated by James Balowski for the Indo-Left News Service in partnership with the Pacific Media Centre. The original title of the article was “Hari Pers Nasional: Tak Ada Progres Kebebasan Pers di Era Jokowi“.