With the date for this year’s second Fiji general election since the 2006 coup yet to be announced, one of the questions is will there be a free media for the campaign? Sri Krishnamurthi in Suva talks to some media commentators who are not optimistic.

The frenzy of the forthcoming elections is just starting to hit Fiji, even though the date has yet to be announced, but the elephant in the room is whether the media is going to be free of government interference.

“No, definitely not. The combination of threats [such as those faced by Hank Art – who as publisher of The Fiji Times recently beat sedition charges] and self-censorship have become

severe,” says New Zealand journalist Michael Field, a veteran of 30 years reporting on the Pacific.

“I believe the Fiji media is fearful of the [Voreqe] Bainimarama government and its ability to hit at media in ways that are expensive and worrying. This ranges from the simple banning of government ads in The Fiji Times to the various sedition issues.

READ MORE: Coups, globalisation and Fiji’s reset structures of ‘democracy’

“Being free and independent is too expensive for what are small companies compared with the size of the state.”

Dr Shailendra Singh, coordinator of journalism at the University of the South Pacific, questions whether Fiji is ready for a free media.

“Whether Western notions of free, unrestrained media are suitable for a developing, fragile, ethnically-tense country is a moot point,” he says.

“Media have been known to inflame situations, just as governments have been known to use stability and security as pretexts to curtail media scrutiny and criticism. Finding the right balance can be elusive,“ Dr Singh says.

‘Power of the pen’

When Sitiveni Rabuka staged the first two coups in 1987, he admittedly was unaware of the “power of the pen”.

“Personally, I had nothing to hide from the media” he said on reflection in 2005 about his coups.

However, subsequent governments did not see the media as a poodle to be toyed with; instead the perception of the industry was that of a rottweiler itching to bite.

“I think it is more likely that the media regulations arose from those who saw the influence of the media, particularly in the [Mahendra] Chaudhry government [overthrown in the third coup in 2000] – and earlier in the lively free-ranging days when the media really was free and independent,” says Field, who was banned from Fiji in 2007.

“The Bainimarama government is clever enough to realise that they might not last with a free media.”

Fiji has flirted with having both a regulated media and self-censorship since the first of its four coups in 1987.

“True. But the government baulked, fearful of the public reaction and international fallout,” says Dr Singh.

‘Media always fragile’

“What that tells us is that media freedom in Fiji has always been fragile. It was only a matter of time.

“Media in Fiji are free to report as they see fit but serious mistakes are punishable by various existing laws such as defamation and contempt which are sufficient, so journalists are quite cautious.

“No one wants to be dragged through the courts like in the recent Fiji Times sedition case. The three-year lawsuit would have been financially, physically, psychologically draining. The Fiji Times escaped by the skin of its teeth.

“Free media is in the beholder’s eyes in some respects. Government feels media is free enough. Media, on the other hand, feel caged. Finding the right balance can be elusive.”

Ricardo Morris, a former journalist and current affairs magazine editor in Fiji, explains the impact of the Media Industry Development Decree (MIDD) which was imposed in 2010 and five years later became law.

“The decree became an act in 2015. The Media Authority (MIDA) doesn’t have to do much anymore because [chairman – Ashwin] Raj simply has to make comment or criticise a media company for some perceived slight and everyone retreats,” says Morris.

Morris researched and authored a 2017 report on self-censorship in Fiji on a Reuters Foundation scholarship.

“There is talk regionally and internationally about how the media Act is hanging over the media’s head. However, Raj usually says, ‘we have never brought prosecution against a media company under the media decree’ and he is right.

‘Always that danger’

“But there is always that danger.

“They’ll usually issue statements, and in the past there has been public shaming, so now you don’t really need to bring cases against the media because they are too afraid to do something that might jeopardise their position or if they do get charged they will get charged under some other criminal law as in the case of The Fiji Times now – they are charged under the Crimes Act, a case that has now gone to appeal. That’s a distinction.”

Dr Singh says it is for that reason he does not see a relaxation of the media laws.

“The media situation is not going to change – that I can say with some confidence. The laws are going to remain the same for some time yet.

“Government, which has the power to change the legislation, has not said anything. One assumes the government is happy with the way things are, so why change? If this government is returned with a strong mandate, it may feel confident enough to change the laws.

“Or it may see a stronger mandate as a vindication of its media law. The opposition National Federation Party (NFP) has said it will abolish the decree if it forms government. “

Which provisions of MIDD do those involved find most objectionable and would like to see removed?

‘Protect their own backs’

“Fines and jail terms against reporters/journalists were removed but this is meaningless unless the same is done for publishers/editors, obviously because the latter have control over journalists and will censor them to protect their own backs.

“Clear definition of what constitutes inciting communal antagonism,” says Dr Singh.

As Field says, it is simple case of economies of scale when it come to the media.

“This ranges from the simple banning of government ads in The Fiji Times, to the various sedition issues. Being free and independent is too expensive for what are small companies compared with the size of the state,” he says.

Hence the media has become a cowered and beaten animal in Fiji.

“It has become tame and fearful, it is under the control of the government and its handlers. Many journalists in Fiji, with an eye to junkets and scholarships, prefer to follow the Information Ministry line and just write up press statements,” says Field.

“I don’t think there has been a true debate in Fiji over what a free media should be … the debate has always been defined by the men with the guns.”

Sedition charges

Sedition charges were filed against The Fiji Times, three of its executives, and one opinion columnist. The columnist (Josaia Waqabaca) accused Muslims of historic crimes including invading foreign lands, rape, and murder.

“Sedition is not a crime in most countries, it’s called free speech. The content of the letter with its anti-Muslim sentiment is widely held by many. By suppressing it you do not make it go away,” says Field.

“I believe the final verdict was reached because the open absurdity of the charge, and its contents, could not be sustained, and even the imported judge did not want to be seen signing on to it.”

As Morris puts it: “We haven’t really heard the debate about the sedition law, a lot of the countries with similar histories have abandoned the sedition law because there is a fine line between freedom of expression and sedition.

“But now because of The Fiji Times, my perception is the general public err on the side of caution and will not say anything that will be deemed seditious.”

MIDD sits above the media like an axe waiting to fall, and the threat of it falling is why the media cannot expect freedom in the 2018 general elections or anytime soon.

- Fiji is ranked 57th on the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders world press freedom index with an RSF verdict: “Little desire to restore media freedom”.

Sri Krishnamurthi is a journalist and Postgraduate Diploma in Communication Studies at Auckland University of Technology student contributing to the Pacific Media Centre‘s Asia Pacific Report.

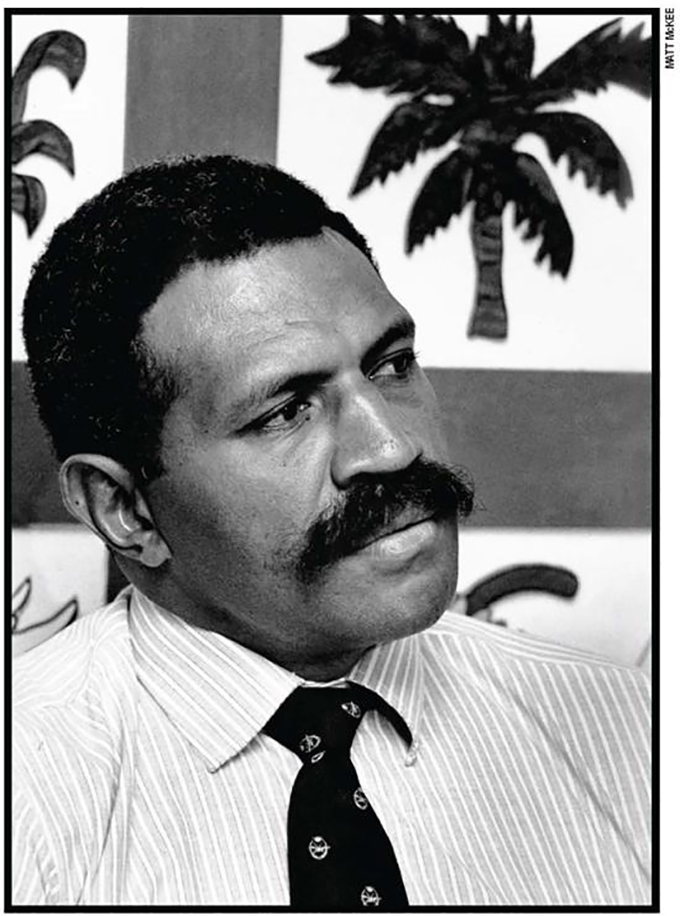

Sri Krishnamurthi’s interview with former MIDA chief executive Matai Akaoula, now a FijiFirst MP.

[…] Source […]

Comments are closed.