ANALYSIS: By Steve Sawyer

Looking back at 2016, it’s easier to come up with a list of bad things that happened than good: Brexit, Trump and the rise of post-truth politics; the Syrian disaster, and the subsequent European bungling of the influx of refugees; and China and Russia flexing their military muscles on the borders of Europe and in the South China Sea.

Closer to home in the United States for wind we have the Brazilian political and economic disaster leading to zero auctions for new capacity; continued increase in the outrageous curtailment in China; and corruption at the highest level in South Africa trying to kill the renewables industry just as it starts to bloom. The list could be much longer.

But there is plenty to be positive about as well: record low onshore prices in Morocco (less than $0.03/kWh); 12 months ago in Argentina we had nothing — now there’s a solid 1.4GW pipeline, which will be added to in 2017; despite the politics, the US industry is arguably healthier than it’s ever been, with record capacity under construction; the Australian market has come back to life; and amid the general European malaise, offshore prices have cratered in the past six months. Offshore wind’s prospects are now brighter than ever, not least because prices make it likely that the industry will expand outside of Europe in earnest in the coming years.

So what’s in store for 2017?

First of all, the US: the only thing I can say at this point is that I don’t know what they’re going to do, and I don’t believe that they do either.

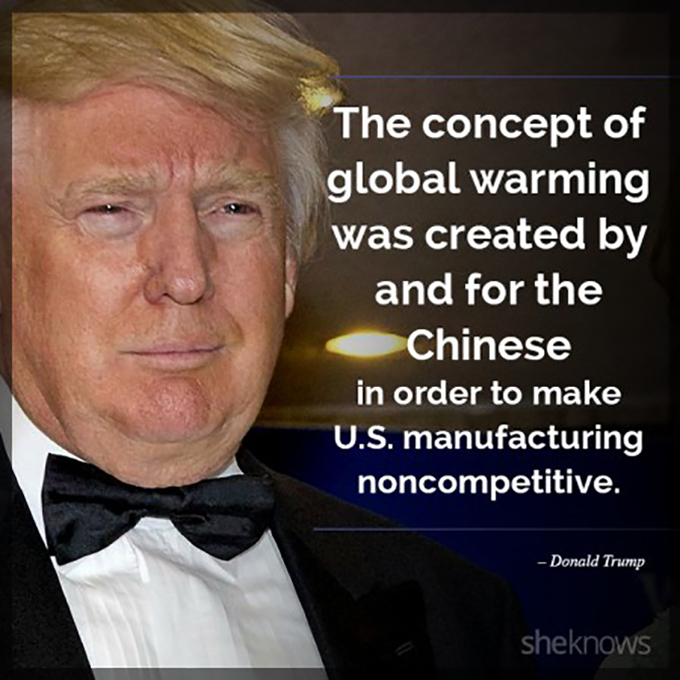

Donald Trump has now appointed a bunch of climate-denying billionaires as his key cabinet nominees — the confirmation hearings will be interesting; and in his “conciliatory” New York Times interview, he spewed such a load of nonsense about wind power it’s hard to know where to start.

On the bright side, energy secretary nominee Rick Perry is the former governor of Texas, and in that role at least was a big wind supporter. More than 80 percent of US wind installations are in Republican congressional districts, and key Senate figures have vowed to oppose any moves to undo the production tax credit deal done last December.

Whether that resolve will hold in the face of the coming whirlwind remains to be seen. Given the level of construction activity at present we would expect 2017 to be a good year for the US market.

Both the International Energy Agency’s Medium-Term Renewable Energy Market Report 2016 and the World Energy Outlook 2016 are quite bullish on the outlook for wind power in the medium to longer term — to the point where the IEA’s 450 scenario is beginning to look a lot like our Global Wind Energy Outlook’s moderate scenario.

The wind industry and the IEA’s outlook have moved a lot closer over the past several years, and I’m happy to say that most of the movement has been on their side.

That said, it is still curious that for the short to medium term, the IEA’s scenarios always posit that the year that has just finished will be the largest market ever for wind power, and 2016 and 2017 are no exception, with predictions of double-digit drops from 2015 market levels for both years.

In the world’s largest market for wind, the downward revision in China’s feed-in tariffs at the beginning of 2018 means there will be another rush of installations in 2017 to beat the deadline. The move to shut down coal plants and even cancel some plants under construction will not solve the curtailment problem in China, although it may help a bit; and the ongoing “airmageddon” in Beijing and elsewhere only boosts the call for clean energy as the country wrestles with its killer air pollution.

The cancellation of Brazil’s auction in December was the latest signal that its wind industry is another potential victim of the political and economic crisis that has occupied the country for the past year. As a result of the stringent local-content requirement attached to the only realistically available Real-denominated financing (from the BNDES national development bank), many OEMs have invested in factories in Brazil. But now that demand has dried up (temporarily, I believe), those investments are at risk.

Looking south to the burgeoning market in Argentina, the Brazilian industry is hoist on its own petard, because its local-content requirements make Brazilian-made turbines uncompetitive. It’s going to be a couple of very hard years in Brazil. Even though the build-out from the previous auctions will keep the installation numbers up for 2017 and a bit beyond, without new orders the supply chain will start to fall apart.

The refusal of South Africa’s state-owned utility Eskom to sign power-purchase agreements for the fourth round of the REIPPPP tenders for more than 18 months now is just another facet of the moral and political bankruptcy of the Zuma government. The publication (four years late) of the updated Integrated Resource Plan shows clearly that the cheapest and cleanest way forward for South Africa is based on wind, solar and a little gas, with no need for nuclear until 2037, if ever. However, shortly after its publication, Eskom defiantly put out a tender for a new nuclear plant. There are many other narratives at play in this unfolding drama, but it will probably get sorted out during the course of 2017 and the market will flourish again.

Elsewhere, we see strong markets developing across South America, especially in Argentina, Chile and Peru. Mexico continues with its own energy revolution, and the Canadian government’s rediscovered commitment (pipelines and tar sands notwithstanding) to the climate issue bodes well for that market.

If India is able to recover from the government’s spectacularly disastrous attempt to flush the “black” money out of the system — the so-called demonetisation exercise — then we should see a strong market in 2017, following on from significant market growth in 2016.

There are also stirrings in Vietnam, Indonesia, Iran, Colombia, Senegal, and elsewhere across Africa, Asia and Latin America, which should be enough to occasionally distract us from the political messes in Europe and the US.

But we will inevitably be preoccupied with Trump. After signing on to a letter to President Barack Obama in late 2009 saying, “We support your effort to ensure meaningful measure to control climate change… if we fail to act now, it is scientifically irrefutable that there will be catastrophic and irreversible consequences for humanity and our planet”, Trump spent most of the campaign talking about climate change as a Chinese hoax. Go figure.

The response of most of the rest of the countries at last year’s climate summit in Marrakech was that they were moving ahead regardless of the US. The Chinese delegation emerged as the somewhat reluctant global leaders of the climate effort, and reminded Trump that the establishment of the IPCC and the beginning of multilateral efforts on the climate issue were instigated by US president Ronald Reagan and UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

Post-truth politics, indeed.

Steve Sawyer is secretary-general of the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC).