The Invisible Picture Show, an animation made by End Child Detention on Vimeo.

Basic rights for refugee children is an issue troubling some South-East Asian nations. In Indonesia, more than 800 asylum seekers have been identified as children, while in Malaysia, close to 300 children out of the country’s 12,000 asylum seekers are seeking refuge. Jihee Junn looks into the issue for Asia Pacific Report.

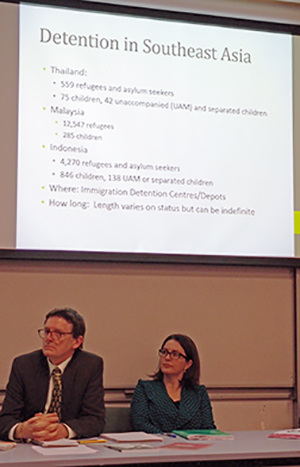

With hundreds of children currently in detention in the Asia-Pacific region, a panel of experts has said that ending child detention could be the starting point to help the refugee crisis.

In a discussion hosted by the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN) in Auckland this week, the global campaign to help end child detention was introduced, as well as alternatives to current detention practices in the region.

![]() The End Immigration Detention of Children campaign advocates for support in New Zealand, calling for all refugee, asylum seeker, and irregular migrant children to have basic rights such as the right to be looked after and to be with their parents.

The End Immigration Detention of Children campaign advocates for support in New Zealand, calling for all refugee, asylum seeker, and irregular migrant children to have basic rights such as the right to be looked after and to be with their parents.

The issue is most prevalent in South-East Asian nations. In Indonesia, more than 800 asylum seekers have been identified as children, while in Malaysia, close to 300 children out of the country’s 12,000 asylum seekers are seeking refuge.

“If you look at the numbers, they’re not massive so we do feel it’s something that is manageable and it could really be a first positive step in advancing refugee protection in South-East Asia,” says Julia Mayerhof, executive officer of the refugee rights network.

Speaking in the context of New Zealand’s potential role in the issue, the chair of APRRN’s Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Working Group, Paul Power, says that the country could use its unique regional position to help with funding or expertise.

“Child detention in the region is a really strategic way to start that conversation [about resettlement]. No one thinks children should be detained and it’s a great starting point for these complex issues.”

Appalling conditions

Speaking from Melbourne where he is now resettled, 26-year old Habib from Afghanistan recalls his experiences in an Indonesian detention centre where he shared the same facilities as many families and children also seeking asylum.

“I think detention of children in Indonesia is not the right thing. It was very overcrowded and it was not actually the right place for them to be.

“We had to bear all kinds of arguments and conflicts because people were sitting together having discussions … I was feeling very sorry for families. For me, I could tolerate some of the arguments, but for the families I think it was very difficult.”

Julia Mayerhof says that such circumstances for children are not unusual. Children are often faced with poor sanitation, insufficient food, and health issues such as skin diseases and tuberculosis.

“People are sometimes allowed to go outside, while in some detention centres there’s no way to go outside at all so they would never see the daylight,” says Mayerhof.

“No sports, no access to education, so everything that a normal child should have to grow up in a normal way, it doesn’t happen in a detention centre. This is bad for adults but for children it’s even worse.”

Unaccompanied minors

Unaccompanied minors — those travelling without a parent or adult — would often face similar circumstances to what Habib witnessed, although there are exceptions.

“There are a lot of countries where they’d be detained in the same environment as adults,” says Dr Robyn Sampson, senior adviser and research coordinator at the International Detention Coalition (IDC).

“But there are some great examples of countries that do not detain unaccompanied minors because they would be so vulnerable, and the Philippines is a good example. They actually place these children in the mainstream child protection system that they have set up for their own children who don’t have parents or adults to look after them.

“In my opinion, one of the ideal outcomes for these young people is to go into the mainstream protection system that might involve foster care,” says Dr Sampson.

“Another example is when they go into shelters, and that can be good because they are with other young people who have had the same kinds of experiences and may even speak the same language.”

But despite these alternatives, lack of capacity has become a recurring issue, which Dr Sampson cites as one of the main problems with the case management programme in Malaysia.

“This programme is helping to keep these children from being placed in detention in the first place and it’s something that could be expanded in the future.”

“But at this stage, the resources are too low. So although they’re managing to keep children out of detention, they’re not managing to get children who are in detention to be released because they don’t have the capacity.”

Seeking alternatives

In addition to the global number of designated refugees passing the 20 million mark, there are also around 2 million asylum seekers and more than 40 million internally displaced people.

Paul Power says that because of the issue’s scale and complexity, there is simply no single set of solutions. Instead, national, regional, and subregional answers should be sought on particular issues.

“A big problem that the world faces is the tradition of durable solutions for refugees. Voluntary safe return after a conflict has ended and integration in a country of asylum and resettlement are in such short supply,” he says.

“Around 100,000 out of 20 million refugees were resettled. So if you’re waiting on resettlement as the answer to your displacement, you’re going to be waiting two centuries at the back of the mythical queue that many Australian politicians believe.”

Asia and the Middle East stand out as the two regions in the world where most countries have not signed the refugee convention, and with 76 percent of refugees living outside of camps in Asia, the international community must look beyond simply ending detention.

“The situation of refugees in camps is of critical importance and lack of support for people living in these camps is a major factor in the misery of people who’ve sought refuge” says Power.

“But that’s not where most refugees around the world are at. They’re trying to survive in urban settings and most of the international support does not actually take account of that.”

Jihee Junn is a postgraduate student journalist at Auckland University of Technology and is on the Pacific Media Centre’s 2016 Asia-Pacific Journalism Studies course.

[…] From the Asia Pacific Report: “NZ could play key role in ending child detention, say refugee advocates” […]

Comments are closed.