Report by Pacific Media Centre

Brian Fitzgerald reviews the new documentary exploring the origins of Greenpeace.

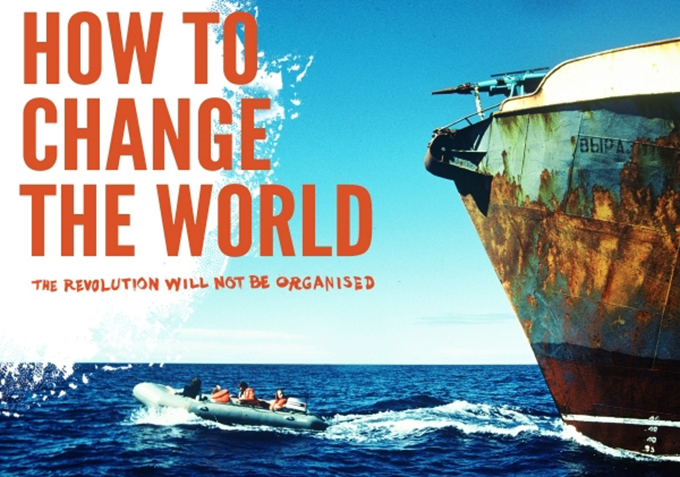

The documentary film How To Change the World has just splashed out on cinema screens in nine countries. It is by far the best telling of the origin story of Greenpeace I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen a few.

As someone who has been with the organisation since 1982 – nearly three quarters of Greenpeace’s life and more than half of my own, I’ve been reflecting on what’s different and what’s unchanged today from the organisation I joined. To answer that, I have to begin at the beginning.

It was the winter of 1980. I was living in a cabin in the woods with no electricity, no running water, no TV. WiFi and internet were yet to be invented.

The snow had been piling up for weeks, and what was normally a couple hour’s hike to the nearest town and back could no longer be completed in the little daylight New Hampshire had to spare in January. I was running low on supplies.

But worse, I was running out of books. When I had finished reading everything I’d brought with me and started on the modest shelf left behind by the owner and the cabin’s seasonal occupants, I picked up something that would change my world. Despite being as far out of the media mainstream as anyone could be, I got hit right between the eyes with a “mind bomb” that had been detonated 10 years earlier.

The book I picked up that day was Bob Hunter’s Warriors of the Rainbow. It was the story of the founding of an environmental activist group I had never heard of before called “Greenpeace”. I was mesmerised.

The book I picked up that day was Bob Hunter’s Warriors of the Rainbow. It was the story of the founding of an environmental activist group I had never heard of before called “Greenpeace”. I was mesmerised.

Here was a group going out and confronting some of the greatest forces on the planet, exposing environmental abuse where it was happening, packaging up those stories for the medium of the day, television, and hurling them into the zeitgeist like cultural hand grenades full of dandelion seeds.

Forbidden zone

Whether it was a boatload of peace activists sailing into the forbidden zone around a nuclear weapons test site or a tiny rubber boat defying a harpoon or mud-covered monkey-wrenchers shutting down a toxic waste pipe, they were creating simple, black and white stories of ordinary people who believed a better world was possible, standing up against the impossibly powerful forces of militarism, social conformity, and profit-at-any-cost capitalism.

Like artists, they were amplifying the weak signals so many were picking up on that something was amiss with our relationship with nature. It’s hard to believe today that this was once a genuinely new idea.

Every one of those stories, implicitly or explicitly, asked a simple question: There’s the harpoon, there’s the activist. What’s going to happen next? And which side are you on?

When I answered that question, I took a step over an invisible line. I became an activist. Millions of people did the same in reaction to the stories that Greenpeace told, the work of Rachel Carson, Edward Abbey, the Sierra Club, CND, artists, singers, culture hackers and relentless investigative journalism that exposed atrocities of human suffering and inhumane abuses of nature.

On the back of all of that, a movement was born.

Bob’s story of Greenpeace’s beginnings is now being retold in Jerry Rothwell’s award-winning documentary, How to Change the World. It’s the story of a rag-tag mission to stop an American nuclear weapon test in Vancouver’s backyard and how it became one of the world’s most powerful environmental organisations. One which was forged in the oppositional politics of the North American anti-war movement, tempered with the social upheaval of a global youth rebellion, and infused with the mystic hippy conviction that alternate realities co-exist with and can sometimes overtake the monolithic consensual hallucination we call “the way things are.”

Both the book and the film are endearing, and enchanting, glimpses into the brilliant and bumbling adventures of a group of friends, “not all of them brave or good,” as they literally set course by following the moon and chasing rainbows, making history along the way.

Greatest strength

Arguably, the naivety of which they were accused was their greatest strength: they were a bunch of young people who thought they could change the world. Not knowing any better, they did.

It’s a story of a different time, and a different organisation.

Or is it? Over the course of my 34-year voyage under the Greenpeace flag, the world has changed profoundly. The cold war ended. Nuclear weapons tests, whose fallout was once declared “perfectly safe” (until it started showing up in children’s teeth) are no longer a fortnightly global ritual.

Antarctica was declared a land of peace and research, off limits to oil and gas exploration. Radioactive waste is no longer dumped into the sea. The commercial hunting of whales has been reduced to a tiny fraction of the former wholesale slaughter. The ozone hole is in retreat.

Entire classes of toxic chemicals that were once simply dumped into rivers are now banned. Greenpeace and the work of hundreds of other organisations and the decisions of millions of individuals made these things happen, all sprung from the same inspiration that moved Bob and his bedraggled boatload of fellow activists.

And Greenpeace has certainly changed. Telex machines have given way to tweets. We speak to a globally connected audience in memes and viral video. Our ships can broadcast, live, from any ocean in the world rather than waiting weeks to deliver film rolls to shore.

The organisation has spread from two North American offices that squabbled like teenagers to have presences on every continent with some of our most important work being done in China, Brazil, India, and Africa. We’ve learned, imperfectly, to squabble like adults.

Reaped rewards

We’ve also reaped the rewards, and paid the price, of becoming an institution in the global spotlight. Our name is a calling card that will get us in the door at most corporate headquarters — though often with an additional security check. Through the generosity of millions, we’ve been able to keep three ships and offices in 55 countries going without soliciting or accepting corporate funding.

Greenpeace is the most recognised name in environmental activism, to the dismay of organisations that work for decades on an issue only to have Greenpeace get all the press, and to an entire movement’s peril when we publically fail, as we sometimes do, to live up to the values we champion.

When I look at How To Change the World, I think the biggest shift is in that early, uneasy balance of power between what Bob called the “mystics” and the “mechanics.” The mechanics won, hands down. The last time I saw a copy of the I-Ching on a Greenpeace ship it was my own. Spiritual journeys or magical coincidences — beyond the occasional rainbow’s arrival on the scene at precisely the right time — tend to be kept below the decks and under the table rather than being a part of planning meetings.

Maximizing wind power, fuel efficiency, overheads, and arriving on time in a port are what determine our ships’ courses these days. There’s no chasing moonbeams, and there are fewer people about who would align themselves with Bob’s belief that “we were part of a reflex, summoned to action by the Earth itself.”

Greenpeace is an organisation dedicated to change, and one which has perennially changed itself to meet changing times.

Steve Sawyer, a former Greenpeace leader and mentor to many Greenpeace activists of my generation, remembers talk of the “good old days” as far back as the 1970s. But to my thinking, there’s one thing that hasn’t shifted a millimeter from when we started, and that’s the story at the core of Greenpeace.

Steve Sawyer, a former Greenpeace leader and mentor to many Greenpeace activists of my generation, remembers talk of the “good old days” as far back as the 1970s. But to my thinking, there’s one thing that hasn’t shifted a millimeter from when we started, and that’s the story at the core of Greenpeace.

We may tell it in different voices, in different mediums, and through different actions. Where once we disdained the idea of ever taking our story to the boardrooms of our “enemies” or to any audience that required we wear a tie, we learned to work the levers of those strange machines. We learned the story was strong enough to go anywhere.

Simple story

The Greenpeace story is simple. It’s this: We believe a better, more sustainable world is possible, and that brave collective and individual action can bring it to life. What we say today is exactly what we said in 1972: we can change the way we feed and fuel our world, we can live in greater harmony with our planet and ourselves. It’s that simple.

If there’s a change in the wind these days, I’d say it’s being truer to that message than we ever have been. It’s reminding ourselves collectively that what binds us all together, whether we got involved 30 years or three days ago, is the fierce optimism of belief that change is possible, despite the apparent odds.

When it comes to real change, the long view is the only one that matters. Whether it was the overthrow of Apartheid, India’s struggle for independence, the civil rights or women’s suffrage movements, every one of those movements was once dedicated to a seemingly impossible goal.

Greenpeace has been an effective voice of alarm, a voice of anger, a voice of “no,” a voice of “stop.” The world is heeding, albeit too slowly, that warning.

At some point, however, shouting “FIRE” in a burning building starts to get in the way of actually putting it out, if that’s all you do. Today, we’re more defined by what we stand against than what we stand for. Yet at it’s core, the story we tell is fundamentally one of hope, optimism, creativity, and courage.

What does the green and peaceful future we want actually look like? That’s a question I would love to see all of us who believe in a better future tackle together.

A friend reminded me the other day of William Gibson’s saying that “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed”.

Social obligation

A future which can support 7 billion people without destroying our future is already out there. It lives in Elon Musk’s decision to open source the Tesla electric car and the “Powerwall” batteries which will enable intermittent renewable sources to reliably power entire buildings.

It lives in Costa Rica’s decision to abolish its military and repurpose its resources toward health and education. It lives in The Guardian’s “Keep it in the Ground” fossil fuel divestment campaign – a thrilling acknowledgment that truth-tellers have a social obligation to activism when it comes to global peril.

It lives in adventures like the Solar Impulse’s historic crossing of the Pacific in a sun-powered plane without a drop of fuel, in ambitious prototypes like solar bike paths and solar roadways, in buildings fitted with vertical organic farms to feed their occupants, in the sharing economy, in the global investment community that added more new renewable energy capacity last year than oil, coal, and gas combined.

All that evidence reminds us that the most relevant lesson from How To Change the World to Greenpeace today is rule #5: Let the Power Go.

As Paul Watson says in the documentary, “The real lesson of those days is that a small group of people can make a difference without many resources.”

That’s never been truer than today. New ideas can travel the world at the speed of thought. Government policy and corporate behaviour can be changed by a few inspired people and a hashtag.

Any force strong enough to truly change the world won’t be harnessed or held. It has to be unleashed.

Power to change

The power to change our future doesn’t reside with Greenpeace, the environmental institution, it resides with every human being confronted with the fiercely urgent evidence that we need to embrace transformational change, or perish in our commitment to business as usual.

The forces of an entrenched status quo, be they oil companies, coal barons, or the beneficiaries of an economic system more attuned to greed than need will tell us that change is impossible. That it’s too expensive. That it’s naive. That those hippies in that documentary were wrong, misguided.

The forces that believe a better world is possible say otherwise. We say that when people in large numbers come to believe change is possible, change becomes possible.

Which side are you on?

Brian Fitzgerald is a story adviser at Greenpeace International in Amsterdam. This blog article is republished with permission.

—